|

|

|

|

|

|

![]() |

1990s: RETIREMENT – BRITAIN

Bernard and I retired from the University of California in June 1989, and moved to England at the end of that year. A strong reason for moving to the UK was Bernard’s health, already a cause of concern when we lived in California. Because of his interrupted university service, Bernard had no medical aid, so we thought it prudent to move to England, where he could take advantage of the National Health Service.

Initially we considered moving from our Kennington flat to a grander home in north London, where most of our friends lived. I had even looked at some properties in Islington when I was in England for the wedding of my godson Adam Lister. But when we happened to mention our plans to Neville Rubin he was puzzled, saying, ‘You have a perfectly good London flat already. Why not keep that and buy a small place in the country?’ We immediately realised that he was correct; and at geographer Bernard’s suggestion we decided to look for our country home in the south-west of England, within the triangle of Salisbury, Bath and Exeter – away from the commuter belt, but near enough to London for easy access.

Jim and Deirdre Parker, our Falkland Islands hosts, invited us to stay in their Somerset home while we house-hunted, starting, at Jim’s suggestion, in Sherborne, Dorset. On the first day an estate agent showed us a compact new bungalow (not quite completed) in Newland, within the favoured central ‘conservation area’. Despite having to enter an agonising contract race, we were able to buy the house shortly before Christmas. It had three bedrooms, two bathrooms, a small garden, and a view towards Sherborne Castle. We grandly named it Tanrhocal House – after Tanganyika, Rhodesia and California – and it suited us very well for the decade that we lived there.

By early 1990 we had settled in at our two homes, the ground floor flat in Kennington, and the bungalow at 86 Newland, Sherborne. The journey between Sherborne and London took three hours by road, or two hours by train, and we soon established a regular pattern, spending on average about ten days a month in London. In summer, when London was hot and crowded, and Dorset was at its best, we spent more time in the country.

DWB London, 1990 DWB London, 1990

In winter, when the theatrical and musical seasons were in full swing in London, we prolonged our periods in the capital.

Our relocation to Britain was facilitated by our established network of friends, most of them going back over decades – many with African or overseas connections. Walking in St James Park one evening, we heard a voice behind us: ‘What are you doing, coming to my district without informing me?’ It was Randal Sadleir who had been my District Commissioner forty years before in Handeni, Tanganyika.

During our decade in England, we occasionally took part in academic activities. I attended anthropology seminars, and gave talks – often jointly with Bernard, and usually on our Kenyan fieldwork – at universities in the UK, Finland, Germany, Crete, and the Netherlands. Jan Slikkerveer, the late Mike Warren and I edited a series of ten books on aspects of indigenous knowledge, published by the Intermediate Technology Press.

Both our homes had room for guests. These included many former students from California – we enjoyed showing them our environs. We took Nthia Njeru (from Kenya) to the Tower of London, where

Bernard, Jim Parker, Andy Sugg, unknown, Deirdre Parker Stag’s Head Pub, Yarlington, 1992

he told us he had had no idea how bloody the Tudors had been, saying, ‘I thought that we were the bloodthirsty ones.’ We showed Manesendu Kundu from Calcutta the Oval Cricket Ground, which he had seen on TV countless times.

We continued writing ‘Letters to the Editor’. On Shrove Tuesday 1992, Bernard and I, walking in the grounds of Sherborne Castle, saw a remarkable sight, six hares running in circles, abruptly stopping and reversing direction. They did this three times, then dashed off the field. We wrote to The Times, which published our letter (after telephoning to make sure that this was not a hoax) under the heading of ‘March Hare Madness’. As is usual, our names and addresses were included. The sequel was a telephone call from Jimmy Clark, who lived in Sherborne, asking if I was related to Guy Brokensha. Jimmy had been a pilot in Guy’s Fleet Air Arm squadron, and had been on HMS Formidable when Guy disappeared. This was a great thrill for me, I had never met any of Guy’s fellow pilots. At their annual reunion, we met three other pilots from Guy’s 888 Squadron. All of them spoke affectionately and admiringly of my big brother – ‘Brock’, as they called him – describing him as the best pilot in the squadron.

Tanrhocal House, Sherborne

We used to enjoy Bernard Levin’s columns in The Times, but he shocked me once by referring to ‘frogs, wops and krauts’. I wrote to him, saying that I realised that he was being ‘jokey’, but pointing out that he, as a Jewish man, would not enjoy such derogatory epithets, any more than I, as gay man, would appreciate offensive gay terms. I received a charming, handwritten reply: ‘Thank you for your very kind and gentle letter. I stand rebuked, and I assure you that I have taken note of what you wrote.’

We were regular walkers. When we were in Sherborne, a favourite walk, which took three hours, was a circular route, through Sherborne Castle grounds, and back via small villages. Whatever the season, we always saw something new, as we had done in Kenya two decades earlier. Bernard’s observant eye would spot the

primroses and violets in the ditches alongside the road, or the herd of castle deer, or the pheasants … primroses and violets in the ditches alongside the road, or the herd of castle deer, or the pheasants …

In our first years in London, I ran in the early mornings, either along the Thames or in one of the parks. Bernard continued to swim his mile, going nearly every day to the ‘Queen Mum’, the Queen Elizabeth II Sports Centre, near Victoria.

Walking in London was another regular recreation, one which Bernard kept up as long as he could. We liked to explore the City on a Sunday morning when it was quiet, choosing a sunny day for Bernard’s photography. We used to take hardy

Peter Castro and DWB sightseeing in London.

DWB and Bernard. Sherborne, 1994

500 visitors, who had only a short time in London, on our round London tour, which took a full day, starting early with the Underground to Kew for a quick look at the Royal Botanic Gardens, always popping in on the small Marianne North Gallery, crammed with her vivid tropical paintings. We would then go, above ground, by train in a grand half-circle of North London, via Hampstead and Islington, allowing us to see the great variety of domestic architecture. Our journey ended at the Isle of Dogs, and from there we walked through the tunnel under the Thames, to Greenwich – in time for a pub lunch. Still time to walk up Greenwich to see the old Royal Observatory, where the meridian of zero longitude is located. We liked to photograph our visitors standing with one foot in the western hemisphere, one in the eastern. There would be time for a hasty look at the Cutty Sark, the last of the great clipper sailing ships, before catching a ferry back past Tower Bridge and the Tower of London, to Westminster Pier, for a sight of the Abbey and the Houses of Parliament – and home.

On such excursions, I was proud of Bernard, with his truly encyclopaedic, yet lightly carried, knowledge of all that we were showing our guests, and his ability to answer nearly all questions, even when they were of an arcane character. Especially at the end of his life, Bernard often thanked me, saying he had learnt so much from me, that I had given him so much. I tried to persuade him that it was a reciprocal business – we learnt from each other, not only factual knowledge, but also about behaviour. Bernard made me more cautious, more able to deal with an unpredictable world, and I encouraged him to be more trusting, more relaxed with people. We enriched each other’s lives immeasurably.

We were lucky in our parish priests; at Sherborne Father Michael proved to be understanding, welcomed us into his parish, and was glad to let us help in various ways. I was Secretary of the Ecumenical Council, and Bernard and I ran the book stall at the annual fete. We also directed a ‘Small Parish Group’ meeting monthly, at our home.

Bernard had always encouraged me to go to mass, and in 1991 he decided to take part in ‘The Rite of Christian Initiation’. Every Sunday evening, from September 1991 until March 1992, we joined a small group of lay Catholics learning about their faith, and Bernard was admitted into the Catholic Church at Easter 1992. This was a momentous step, and Bernard’s new faith proved to be deep and lasting. When he became ill in 1993, we had an instant ‘support group’ of friends we had made in the church at Sherborne.

Until Bernard’s death in 2004, our friends at the Sherborne Catholic church continued to keep in touch with us, and to pray for Bernard during his various illnesses. (Despite recent studies showing that prayer does not improve the health of those prayed for, both Bernard and I found great comfort in the knowledge that our friends were praying for us. My own prayers were not ‘Please make Bernard better’; rather, I asked that he and I be given the strength to cope with whatever lay ahead.)

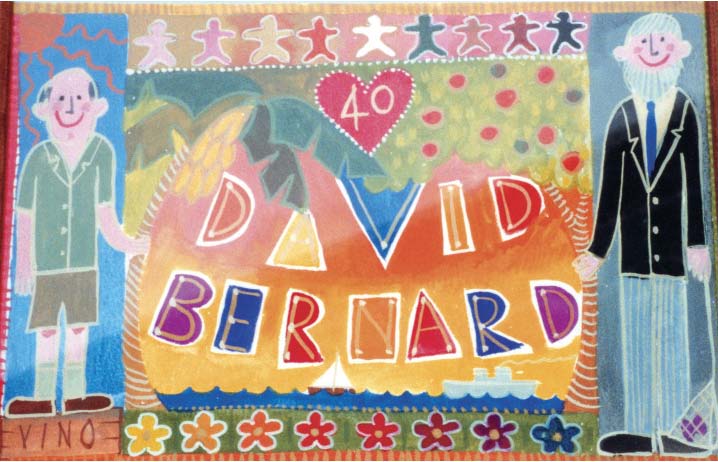

In May 1993 we held a grand party at the rose garden in Regent’s Park, to celebrate my seventieth birthday. We did the catering

DWB (on his seventieth birthday) with his nieces (left) Robin Morris, and (right) Deirdre Blackwood. 1 Kennington Palace Court, 1993

ourselves, with the help of Anne-Marie Shawe and her friends. When we arrived there, I realised that I had left the baguettes behind at our flat, and Bernard rushed off to buy replacements. He rushed so hard that it caused severe chest pains, and when he was checked by the doctor the following day the diagnosis was angina, with heart surgery recommended. Despite this ominous signal, we had a jolly party, and we had another good party there the following year, to celebrate forty years of sharing our lives.

Bernard was advised to have a triple bypass heart operation and, because of the long wait in the National Health Service for heart surgery, we decided to ‘go private’. The operation was done at Southampton Hospital in November 1993. As we learnt later, British hospitals have a high rate of infection, and Bernard developed peritonitis, remaining in hospital for eight weeks, mostly in Yeovil, five miles from Sherborne. He was desperately ill and weepy when Dr Hakeem, from Pakistan, sat at his bedside, held his hand, and gently explained why they had to keep him in hospital until they were quite certain that he was indeed fit. They could not take the

Lyndie Wright’s painting for our fortieth anniversary party in Regent’s Park

medical and psychological risks of sending him home too early for the third time. Bernard was so touched, as was I – no British doctor would have dared to hold a patient’s hand, male or female, for fear of being charged with harassment, or accused of being too sentimental. Dr Hakeem, who was about forty years old, gentle, intelligent, and very professional, said, ‘Do not worry, Mr Riley, we will pull you through.’ A Ghanaian doctor, who knew some of our Ghanaian friends (it was easy for us to establish connections with people from Southern Ghana), also took good care of Bernard.

During the weeks that he was in Yeovil Hospital, I visited Bernard at mid-morning each day, when the over-worked nurses were happy to allow me to help with his bath. I visited again in the evenings, bringing him a tasty dish, as the hospital fare was too bland for his taste. They were a cheerful lot, the Yeovil nurses, who appreciated Bernard for his courtesy, and because he did not make unreasonable demands. One beneficial side-effect was that my journeys to Yeovil, in the dark winter evenings, often in heavy fog, helped me to conquer my aversion to night-time driving.

To keep my anxiety level low, I kept to my daily routine. I used to write regularly to our Santa Barbara friend Pat Griffith, who kept my letters. Part of one of them reads:

6.15 a.m. Up to drink my cup of Rooibos tea.

6.30 a.m. Off for my morning walk, hearing the Abbey clock striking. Walking along New Road, I have meadows (now flooded) on my right, and woods and castles – literally – on the left. The tall, bare, wintry trees are nicely silhouetted against the skyline. At that time of day, there is little traffic, the Brits not being early risers, and I love the feeling of having the whole dark world to myself. I often hear owls, and I imagine, but do not see, it still being too dark, the foxes and badgers that inhabit these woods. Soon after 7 a.m. I see the first glimmers of dawn, I hear the first blackbirds, sounding as though they have truly been ‘surprised by joy’, and I begin to see other early risers – the milkman, Postie on his bicycle, the newspaper delivery boys, a few people walking their eager dogs …

By the time Bernard came home to Sherborne, in February 1994, he was noticeably weaker: he could no longer take long walks, nor could he climb the steps of a double-decker London bus. The Underground was also impossible for him, because in those days some stations had only stairs, and at others the escalators were frequently out of order. Because of angina pain after even moderate exercise, Bernard needed a wheelchair for any distance. As Bernard’s health deteriorated, and his mobility declined, we had to adjust our activities, but, because of his determination and his refusal to ‘take it easy’, we kept up most of our usual activities, both of us quickly adjusting to the wheelchair.

When we were in London, we loved the smaller venues, especially Wigmore Hall and St John’s Smith Square, both of which had a scintillating array of musicians and singers – well-known and young newcomers. We were never disappointed. As a young man, Bernard had been an admirer of the renowned mezzo-soprano Kathleen Ferrier, and had heard her sing several times in wartime Manchester. Wigmore Hall presented the annual Kathleen Ferrier Memorial competition for young singers, the prize being both substantial in money terms and a significant help to a musical career. We attended as many of the Final nights as we could, sharing in the mounting

Bernard enjoying a cider at the Rose and Crown, Trent, Dorset, 1996.

excitement. We went also to St James’s Piccadilly, St Martin’s in the Fields (on Trafalgar Square), and to several small City churches which featured lunchtime concerts of high quality.

For opera, we liked ENO (the English National Opera) because it was more affordable, and less pretentious, than the Royal Opera House at Covent Garden. Over the decade that we lived in London, we had many thrilling evenings at ENO, seeing both new and old operas, as well as jolly, spirited productions of various operettas. The ‘war horses’ – the established operas – were livened up, without losing their musical integrity, and without being too ‘gimmicky’, or too ‘trendy’ – to use two of Bernard’s expressions of disapproval. At most theatres and opera houses, Bernard’s disability enabled us to buy the best aisle seats at much reduced prices: we made good use of the helpful Disabled Guide to London.

We went more often to the National Theatre than anywhere else, both because of the quality of its productions, and also because it was relatively near to Kennington. Indeed, when we were first in London, we would walk there. We also went to the fringe theatres, sometimes leaving at interval when the production failed to grip us; on other occasions, we saw riveting theatre, and we accepted that we had to take some risks.

Our love of the theatre led us to make regular excursions to Bath, to see plays, often ‘try-outs’ for London, at the Theatre Royal. Bath was only an hour’s drive from Sherborne, the route quintessentially beautiful West Country. Our other theatrical target was the Royal Shakespeare Theatre at Stratford-upon-Avon, a three hours’ drive from Sherborne. We would see two or three plays, often fitting in, on the same day, both a matinee and an evening performance, and staying at Avoncroft, a comfortable B&B, in a lovely old seventeenth century house near the church where Shakespeare is buried.

We got to know the London art galleries well, despite some being wheelchair-unfriendly. We were disappointed by the Imperial War Museum, where access was not easy: many disabled ex-servicemen must have had to battle with the handicaps. We eventually worked out where we should park the car for each gallery, and how we could get inside, even though at some places, notably the British Museum, this involved complicated routes. The National Gallery was relatively accessible, but once one was inside, there was another hazard for wheelchair users – the glass swing doors separating the galleries. Unobservant British visitors tended to let the doors close in our faces, and we soon learnt to look out for Japanese visitors, who would smile, bow and hold the doors open for us, then we bowed and smiled in return. Bernard was never put off by these challenges, and we saw virtually all the major exhibitions in London.

A major discovery for me was the London Library, almost on St James’s Square, the largest private library in the world, where I would happily browse for an hour or two, emerging with half a dozen varied volumes to keep us going.

Throughout our stay in London, we continued our habit of lunching out. A main criterion in selecting a restaurant was the outlook: Bernard loved to have a view, and we soon found some favourite places, particularly along the Thames, from where we could watch the river traffic. There was The Anchor at Bankside (where Dr Johnson and Mrs Thrale had supped), as well as numerous other pleasant riverside pubs.

TRAVELS

In 1990, the first full year of our retirement, we spent two months in Australia, visiting my relatives, and our friends, and seeing much of the country. When the Brokenshas were assembling for a group photograph at her party in Adelaide, it was my cousin Doris Brokensha who said, ‘Come along, Bernard, you are an honorary Brokie.’ Bernard was proud of his new designation, as he had been readily accepted, much loved and respected by my family members.

My cousins Peter and Elizabeth Brokensha, who also lived in Adelaide, joined with Doris in planning a full itinerary for us, including travel by train, rented car, and aircraft. My cousins were much involved both in the arts, especially opera and music, and also in politics, having strong radical views: they introduced us to a more enlightened and sensitive Australia than the one we had previously known.

Shortly after our return from Australia, Bernard’s sister Eileen offered us a fortnight’s stay at her time-share in Madeira, where we spent two weeks. Bernard was still able to walk long distances, and we made several excursions, catching the 7 a.m. bus to a selected destination, walking along the levadas (irrigation channels), having lunch at a wayside restaurant, and catching another bus back to Funchal. Right up to the end of his life Bernard was, for me, the ideal travelling companion, eager, observant, knowledgeable, interested in everything, good at social interactions with strangers, prepared to put up with mishaps: ‘Oh, well, “win some, lose some”, as your brother Paul would say.’

The following year, 1991, we made a long tour of Zimbabwe and South Africa, taking our Santa Barbara friend Harriet Carter, then recently widowed, with us. We saw our many friends and relatives,

Harriet Carter, DWB and Bernard, Chapungu Sculpture Park. Harare, Zimbabwe, 1991

and it was while we were in Cape Town that the seeds were sown that led us to settle there at the end of the decade. We made several other trips: to Luxembourg, to Provence, to Crete, and to Sicily. Near Enna, in Sicily we were overwhelmed by the Piazza Armerina site, of which we had not heard, with its brilliant mosaics, which had been buried under mud for more than a millennium, and had only recently been exposed. We had been reading Prince Giuseppe di Lampedusa’s The Leopard and David Gilmour’s The Last Leopard, an excellent biography of Lampedusa, so while we were in Palermo we were eager to see the nearby ruins of Palazzo Lampedusa.

TOP: DWB on the train to Sicily. 1992

ABOVE: Bernard with sculptor Joram Mariga and his wife. Chapungu Sculpture Park,

With Cees Post and his daughters Jessie and Erin. Luxembourg, 1997

The Museo Palazzo Abatellis was well worth the visit – for one extraordinary and luminous mid-fifteenth century painting, of the Madonna, by Antonello da Messina whose work is thus described in the Oxford Dictionary of Art: ‘His religious works show a remarkable ability to combine Northern particularity of detail with the Italian tradition of grandeur and clarity of form.’ We bought a postcard and hung an enlarged and framed copy in our bedroom, and also gave one to our Simonstown parish church. One of the many joys of travelling with Bernard was that we shared so many of the same interests, and that we had the same reactions. On seeing this wondrous painting, we were both silent in admiration, then eagerly examined the painting, which is unusual in its striking depiction of Our Lady as essentially human, without the cloying sentimentality of so many other representations. We were alone in the gallery, and wondered why we had not heard of Antonello da Messina, and why the gallery was not thronged.

We found that travelling on European trains was made easy for a disabled person, a great contrast to Britain, where it was a nightmare. Our travels with a wheelchair were facilitated by the ability to book ahead, and to have ramps in place and porters to assist us. Bernard always worried, once he started using the wheelchair, that pushing it would be too much for me, that it would tire me out, so he particularly appreciated the assistance that we received.

RETURN TO DRESDEN: AUGUST 1992

In August 1992, I attended a conference (of the Society of European Anthropologists) in Prague, and afterwards I visited Dresden, an easy and scenic three hour train ride along the River Moldau. Having only one full day, I hired a taxi, pleased to find that my rusty German was easily understood. When the taxi driver heard my story, he first drove me past the Dresden Hauptbahnhof, where I had spent so many days and nights, then he drove me to Gorbitz, passing the tram terminus at Wolfnitz, which was remarkably unchanged, The western suburbs had suffered little bombing and I recognised many of the old houses and the cobbled streets along which we had walked so many times

LEFT: Dresden main railway station ABOVE: Road from POW camp at Gorbitz to Wolfnitz tram terminus BELOW: Hellendorf, where we stayed in a barn, and washed in this stream in 1945. Photos taken March 1993

The taxi driver dropped me where I thought the POW camp had been and I went to the office of a new factory to ask directions from a pleasant middle-aged woman: this was my moment of truth as I was uncertain what sort of reception awaited me and whether I had indeed found the correct location. The woman was friendly; having been born in 1944 she knew nothing of the camp, but her father had told her that there had been a camp for British POWs over there (pointing beyond the factory). ‘Aber heute sehen man gar nichts da.’ (‘But today you will see nothing there at all.’) She was wrong: I walked over, now certain that this was indeed the site of our camp, and I met all the ghosts of ourselves when young. So many memories came flooding back as I walked to where the northern fence of the camp had been nearly fifty years previously; the fields on which we used to gaze had changed little, but the further view, looking towards Dresden, was scarred by endless dreary Stalinist apartment blocks.

From the camp we used to walk about a hundred yards to reach the main road, and the imposing house on the corner was still there. I walked down the cobbled street – recognising many landmarks – to Wolfnitz, where I called at the new police station to see if I could find out any more details of the camp. The policemen were polite, but as they were all under forty years of age they had little interest in those events of long ago.

I then took a tram from Wolfnitz into the city. The trams have changed little in design and provide an excellent service, one that I wished Britain would emulate. After my satisfactory visit I followed my taxi driver’s advice, riding a funicular railway to the top of a hill, where I found a quiet restaurant for a cold beer and a good late lunch, recalling some of the more meagre meals that we had had all those years ago, and feeling fortunate.

Before leaving, I visited the well-known Frauenkirche, to note how far restoration had gone. The rebuilding was finally completed in October 2005, with many British and American representatives present for the opening ceremony.

While I was there I took a roll of photographs of the site of the camp and its neighbourhood, but I foolishly lost it – was that a Freudian slip? However on a visit the following year I was able to take good photographs. On this second visit, in April 1993, I was accompanied by Bernard, who put his geographical background to good use in helping me to retrace the route we took when we were marched out of Dresden in May 1945. With the help of Jack Mortlock’s notes, we drove through all the small towns, eventually reaching the large village of Hellendorf, located near the Erzgebirge mountains on the Czech border. The place was almost deserted but one man, in his fifties, was putting out rubbish and getting ready to walk his dog. I told him what I was looking for and he said, ‘Yes, I was a small boy then, but I remember that there were two groups of English prisoners of war; one was in the Gasthof Kecjhnich (which

DWB at Hellendorf near the Czech/German border. 1993

was still standing), and the other group was in the big barn that used to stand over there, but it burnt down a few years ago. You can still see the farmhouse.’

From Dresden we went by train to Leipzig, to attend a concert in the magnificent Gewandhaus, which had been lovingly restored after its destruction in World War 2. Bernard had long wished to see this hall, where many of our LP recordings had been produced.

When I told Jake about our return visit, retracing our 1945 journey in Saxony, he was eager to have the same experience, and I planned to accompany him. We also considered visiting Libya, as Jake was keen to see the War Cemetery in Benghazi where Piet was buried, and I was interested in seeing what changes had taken place in the Libyan coastal towns that we had known. Bernard was enthusiastic about the prospects of seeing sites like Leptus Magna in Libya. But Jake became ill, and Bernard was not strong enough to undertake such a journey, so it was not to be.

RELOCATING TO THE CAPE

We visited Cape Town three more times in the 1990s, both to check on the health of Bernard’s sister, Eileen, and because we were increasingly drawn to the Cape. For Christmas 1998, Eileen and her daughter Chris found us perfect accommodation in Sunny Cove, Fish Hoek. It overlooked the ‘catwalk’ – a pedestrian walkway – and the railway line, with the ocean just beyond, literally (even for me) a stone’s throw from our terrace. The Hottentots Holland mountains, twenty-five miles away, frame False Bay. We decided that we would move from England, and that this would be our home, and arranged to rent the house on a permanent basis.

PACKING UP

We were uncertain what to do with Bernard’s unique collection of 35 mm colour slides, meticulously built up over forty years. Many of them had been used for teaching our Environmental Studies courses. The Royal Botanic Gardens at Kew gladly accepted the bulk of these slides, six thousand, that covered Kenya. A further three and a half thousand went to the Botanical Gardens of the Hebrew University in Jerusalem. This still left a balance of over twenty-five thousand, which we took to Cape Town, where, to our relief, the Department of Environmental Sciences and Geography at the University of Cape Town accepted them all, putting most of them onto CD-ROM.

It remained for us to pack up our two homes. During our decade in the UK, with two homes, we had, inevitably, accumulated many belongings. When an English charity reluctantly refused to accept a mattress because it had a small stain, we took the advice of a Fish Hoek friend who pointed out that many poor people in South Africa would be glad of such a mattress, and shipped our all goods to the Cape. Both homes were quickly sold, and we left England on 11 August 1999, for our final destination, Fish Hoek in Cape Town. This proved to be the best move that we ever made.

1999–2007: RETIREMENT – SOUTH AFRICA 1999–2007: RETIREMENT – SOUTH AFRICA

This last period may be divided into three distinct phases – before and after Bernard’s disabling stroke of October 2001, and after his death in 2004.

PART 1 1999–2001

Bernard and I returned to my native South Africa in August 1999. We had made advance preparations, being fortunate in having a network of good friends and relatives in and around Cape Town, and they rallied round us, supporting us during Bernard’s final days, and helping me afterwards.

Coming to South Africa, our good fortune continued. Fish Hoek has a large Catholic church, half a mile from our house, but we felt more at home in the church of Saints Simon and Jude, five miles away in Simonstown, where Father Bram Martijn (from the Netherlands) was in charge. When we first invited Bram to dinner, after our usual Saturday evening mass, he told us, ‘It is beautiful that you are able to support and encourage each other.’ He regards himself as a bridge, he told us, between the old church and the new one. I have no idea how many Father Brams there are out there, but I do hope that there are enough to make a change, some day.

Our home, at 37 Simonstown Road in Fish Hoek, was on the outskirts of this pleasant and quiet seaside town. Many regard Fish Hoek as dull: it has none of the trendy boutiques, antique shops and lively bars of its neighbours Simonstown and Kalk Bay; indeed liquor may not be sold in Fish Hoek, except with meals in restaurants. Clive Rubin, a young friend of ours, asked us why on earth we had settled in Fish Hoek, which he described, scornfully as ‘a community in denial’. However, it suited us down to the ground.

The quotations in this chapter are from Bernard’s letters. He immediately recognised the geographical advantages of our new home:

The Simon’s Town Road runs southward from downtown Fish Hoek along the eastern False Bay shoreline of the Cape Peninsula. This rocky headland is known as Sunny Cove, and is so steep that the railway is confined to a single track. We are in the lee of the steep rocky headland separating Fish Hoek Bay from the open section of False Bay. We face north, with direct sunlight in all the rooms, and we are shielded from the notorious South-Easters. These are chilly, strong, sometimes gale force, winds, which generate over the Antarctic Ocean.

Tanrhocaldor House, as we called our new home – adding the dor for our ten years in Dorset – had been set up as a furnished holiday home. We quickly put up our paintings and arranged the much-travelled Zimbabwean sculptures. Outside is a terrace, ideal for lunch parties and braais (barbecues) in the summer months. From the main bedroom there is a magnificent view of False Bay, with its ever-changing scene: fishermen in their boats and anglers on the rocks, sailing boats – both the popular ‘Hobie cat’ catamarans and the bigger luxury yachts – para-sailors, swimmers, canoeists (on Friday afternoons whole flotillas of canoes would race past us), walkers and runners on the catwalk, children exploring the rocks near the ocean, trains passing by three times each hour from 5 a.m. until 8 p.m. (we soon got accustomed to the trains, and found the sound comforting), whales and dolphins from September to November, and birds galore – common gulls, terns and cormorants, and an occasional albatross, skua or giant petrel. Special visitors are the endangered African black oystercatchers, always in pairs, with their distinctive cries, which Bernard would recognise from his bed. And there are the constantly changing clouds,

and the mountains behind, and the lovely soft evening light on the rocks and moonlight over the bay. This view was important to both of us, especially to Bernard after he became ill and had to spend more time resting in bed. and the mountains behind, and the lovely soft evening light on the rocks and moonlight over the bay. This view was important to both of us, especially to Bernard after he became ill and had to spend more time resting in bed.

Climbing the eighteen stairs became a burden for Bernard, inducing angina pains, so we had a Stannah chair-lift installed. At first, the chair-lift was just a convenience, but, after his stroke, it became essential.

The train from Cape Town going to Simon's Town - from our terrace.

Martin West and Mugsy Spiegel of the University of Cape Town proposed me for an honorary professorship in the Department of Social Anthropology. This suited me admirably: I help in the supervision of postgraduate students, which provides me with mental stimulation, but involves no teaching. I have given an occasional presentation, my first being the annual Monica Wilson Lecture, in which I discussed my first teacher’s impressive contributions to the study of Social Change (Brokensha, 2006). The Social Anthropology Department is small, congenial and its work is of a high standard, with an emphasis on teaching, and with research on what I regard as ‘sensible’ topics. I enjoy the weekly seminars, which are held jointly with the University of the Western Cape. The topics are refreshingly clear and straightforward, certainly compared to the pretentious, self-consciously post-modern ethos of many institutions in the UK

The University of Cape Town. Photo: UCT Communications

and the USA. Topics have included Aids-and-Muslims, township gangs, xenophobia, crime and perceptions of crime, and definitions of racism.

Having located the essential services in Fish Hoek, Bernard and I set about finding a good doctor. Two friends independently recommended Dr Geoff Duncan, the most competent and caring GP that anyone could wish for. Bernard had wanted to continue with mild exercise, so we enrolled at the Sports Science Institute in Newlands. South Africa is, not surprisingly, very advanced in sports medicine, and the Sports Centre is part of a large complex. Our trainer insisted that Bernard see a cardiologist first, leading us to Sean Latouf, who advised him against almost any exercise, and skilfully monitored his health and medications from then on.

Bernard had been justifiably irritated by the often pompous and patronising English consultants, and found the very different attitudes of South African doctors a refreshing change. They treated us as intelligent beings, and were careful to explain the situation, spelling out possible options, telling us of the pros and cons of each. They were approachable and informal, and we were soon on

Bernard with Margaret Thurso. Boulders Beach, 2000

cordial first name terms. From my point of view, it was a refreshing change to be fully accepted as a partner: I was invited to participate in consulting sessions, which had not always happened in Britain, nor in California.

Once we had settled down, Bernard and I both accepted that this would be our last stop. We loved Tanrhocaldor House from the beginning, and never had cause to change our minds – it was the perfect home for us.

Even before leaving the UK, Bernard had applied for permanent residence in South Africa, but the Department of Home Affairs is notoriously slow. Because I had been born in South Africa, I was given South African citizenship on arrival. Our lawyer friend Valerie West advised me to apply to bring Bernard in as my partner, the new, enlightened Constitution having made provision for such cases. Asked if we had been together for two years, we were able to say, proudly, that it was actually forty-seven.

South Africa has an unenviable reputation for its crime rate, and, as if to confirm the stereotype, we had two burglaries, in 2001 and 2002, neither, fortunately, involving any violence. We treated these as wake-up calls, and with the guidance of our landlords, improved the security. We had neither heard nor seen the burglars, but on the second occasion they left our carving knives outside our bedroom, presumably for use if we woke up. Bernard responded calmly, despite knowing how vulnerable he would have been had he woken.

TRAVEL

Ten days after our arrival, Bernard and I set off on our first safari, to see one of the Western Cape’s most spectacular sights, the spring wild flowers in Namaqualand, near the Namibian border. We based ourselves in Kamieskroon, and had three days of rewarding flower viewing, with Bernard taking some stunning photographs with his new camera. He also put his newly-acquired library of books on the flora of the Cape to good use, and busily identified each new wild flower that we saw.

Then we headed for Hantam Karoo, where the higher elevation supported different species of wild flowers. As Bernard wrote:

… our planned trip northward was cut short by a major storm that gave a rime of unseasonably late snowfall on the crests of the Cederberg, and other high spots. It was perishingly cold, and few South African homes are adequately heated. The weather forecast was gloomy, so we drove straight back home.

By then Bernard had a poor tolerance of cold, a contrast to his younger days, when he had seemed impervious to low temperatures. Then, it had been he who warmed me: now, the situation was reversed, and in bed he would snuggle up to me to get warm.

… we could not have timed our return better, for we were awoken during our first night home by a pod of Southern Right Whales, frisking, ‘blowing’ and snorting in the bay … in the morning we were treated to a prolonged exhibition of fin-flapping, tail-slapping, roll-overs and tail stands with the front half of the body held vertically above the rolling breakers … we could not be certain, but we think that there were at least five whales.

We made wild flower excursions every spring, although in the latter years we would make only day trips – to Darling or Langebaan, on the West Coast, both easily accessible, and rewarding.

Shortly after we arrived, the area around Fish Hoek witnessed disastrous fires, fortunately causing no loss of life, but doing enormous damage to property – and to the vegetation. Bernard became an enthusiastic supporter of planting more indigenous species, and removing alien species such as pine, eucalyptus, and especially, the imported and ubiquitous Australian Port Jackson. These alien species not only use up the groundwater, but are also detrimental to the indigenous fynbos, which makes up four fifths of the unique Cape Floral Kingdom, which covers a small part of the Western Cape.

In November 2000 we drove to Silvermine Conservation Reserve, in the hills behind Fish Hoek, having heard that new flowers had sprung up after the fires. At that time, Bernard could still walk, albeit with difficulty and with the help of his walking frame. He walked the two hundred yards to a small dam, where he photographed the cerulean and white water-lilies, which we used for our annual Christmas card.

At the dam, Disa orchids were there in abundance: we found several species nodding at each other with exuberance at their release to complete their life cycle. The fire that destroyed the pines has been a blessing in disguise for the indigenous annuals and biennials, some of which had been dormant for a quarter of a century.

Shortly after our arrival, David and Elspeth Jack bought a farm, Appelsdrift, in the Overberg, which became our favourite destination, both because of the Jacks’ hospitality, and also for the grand scenery

David Jack and Elspeth Jack

and the tranquillity. Driving out of Cape Town, on the national road, the N2, you suddenly see, from the top of the pass at Houw Hoek, one of the great vistas of Africa. As you descend to Bot River, more and more of the landscape opens up, fringed by the Sonderend Mountains in the background. We never ceased to be delighted by the views, beautiful at any season.

When the Jacks bought the farm, the homestead was a broken-down small farmhouse, which David, an architect, soon transformed into a sprawling, and comfortable dwelling, and their son, Bruce, began growing vines for his Flagstone winery. In January 2006, however, one of the frequent bush fires destroyed nearly all the vines at Appelsdrift. Our friends calmly started again from scratch, despite losing five years of loving care of their vineyards.

During our stay in Kenya, we had become enthusiastic birders. In August 2001, a month before Bernard’s first heart attack, we spent a week at Knysna, on the picturesque ‘Garden Route’. Bernard had once seen a trogon in Kenya, and on this trip I was fortunate enough to have my first sighting, and we were both thrilled. Bernard described it in some detail:

An Information Bureau member annotated our visitor’s map to indicate the best bird-watching locations, especially those accessible to an elderly wheelchair-using ‘twitcher’. She recommended The Garden of Eden, east of Knysna, in a pocket of coastal closed-canopy indigenous forest, which included a boardwalk designed for physically handicapped visitors. This was one of the few remaining patches of indigenous forest left, after the extensive extraction of valuable timber in the nineteenth century … I saw, perched on a branch, a rather dumpy, immobile bird, which is described thus in the Twitcher’s Bible: “ Narina Trogon (Apoloderma narina) 30–34 cm. Although brightly coloured, this furtive species is difficult to see, as it normally sits with its back to the observer, well camouflaged by its leafy, green surroundings. Habitat: riverine and ever-green forests of dense, broad-leafed woodland. A locally common resident, but, by its usual immobility, often overlooked.” This was our first avian coup in the Cape!

Bernard in the Garden of Eden, Knysna. August 2001

On this same trip, we decided to see more of the Overberg, visiting Greyton, a charming small town near Caledon:

On our way, we saw a truly amazing sight. Within yards of the road, on a gently rising slope, we encountered a whole gathering, thirty-eight in all, of Blue Cranes, the South African National Bird, now endangered. We had seen Blue Cranes before, singly or in pairs, gleaning in cereal, usually at some distance from us. Their tall, sleek, graceful outlines and distinctive colouring are instantly identifiable.

Out of the car, I could hear a muffled, deep-note ‘Humming’, barely on the threshold of audibility, and I realised that many of the slightly taller and slimmer birds were impatient males. With their beaks slightly raised they moved forward and backward with tiny paces, rapidly beating the ground. The slightly dumpier and somewhat paler females stood their ground. It was an unforgettable sight.

This too became a Christmas card photograph. We were delighted to have had two such rewarding bird-watching experiences during the course of one trip.

Bernard and I loved visiting the Karoo, with its great open spaces, its distant horizons, and the picturesque small towns along the way. We made a major trip to the new Kgalagadi Transfrontier National Park, on the border with Botswana, and to the Augrabies National Park. Both parks were rewarding, especially in terms of the birds and the geology, but we had been spoiled, having visited many Kenyan parks in the 1970s, when wildlife was much more abundant and more varied. However Bernard thoroughly enjoyed the trip, as these extracts show:

Our recent trip northward to the Kalahari fringe was the realisation of a long-held goal for me. I first became interested in the interior of Africa while an undergraduate at Manchester University … Both Alfred Wegener and Alexander du Toit had seriously challenged the standard geological and geo-morphological theories and explanations. Their basic premise was that the Kalahari areas of the Northern Cape and Botswana, as well as the Karoos of the Cape, display irrefutable evidence of a major catastrophic event in earth history. They suggest that the evidence is there in the unique physical features in the landscape.

Water-carved holes in boulders are a hallmark of fluvial erosion, and cannot be explained by occasional deluges of the recent rainfall regime … Kalahari plateaux surfaces rose suddenly. Many areas comprise igneous rock (chiefly basalt) formed in a series of sills from west to east … characteristic of ocean floor spreading, as plate tectonic investigations in the South Atlantic confirm.

Intrigued by searching for corroborative evidence for this controversial thesis, Bernard was constantly and eagerly scanning the vast Karoo landscapes, pointing out features, which, he claimed, supported the cataclysmic theory. I was unable to judge the merits of the theory, but Bernard’s obsession enlivened the journey, and caused me to be more aware of the fantastic geological formations en route. Bernard was intrigued by the dramatic rock formations, especially in the mountain passes.

We made several trips to the Little Karoo, usually driving along our favourite road, Route 62, a broad well-maintained highway, with little traffic. We enjoyed stopping, either for coffee or for an overnight stay, at the small towns of Montagu, Barrydale, Ladismith, Calitzdorp, or in the larger ostrich-centre town of Oudtshoorn. In the early years of the twentieth century most small towns in the Cape had a significant Jewish presence, but one of the synagogues in Oudtshoorn is now a museum – as has happened with other synagogues in the Cape.

On one occasion we drove from Oudtshoorn east to Meiringspoort, whose spectacular rock formations were a source of much wonder and speculation from Bernard; then to Prince Albert, and down the most dramatic of all mountain passes, the Swartberg Pass, and along a little-travelled gravel road to Calitzdorp. This route made us think of what South Africa must have been like in the nineteenth century; it seemed a forgotten part of the landscape, full of ghosts.

While based in Graaff-Reinet, we visited the fabulous ‘Owl House’ at Nieu Bethesda, where the late Helen Martins and her assistant Koos Malgas created a fantastic sculpture collection. We had read Eve Palmer’s evocative book, The Plains of Camdeboo, and had corresponded with the author, who had written: ‘This is a countryside either completely overlooked or greatly slandered; few people visit it, and no-one has ever written about it.’ Driving along the road, all you see is emptiness; but this is an illusion, for one mile off the road is Cranemere, Eve Palmer’s lovely, gracious country home surrounded by large vegetable and flower gardens. Some years later we spent a very pleasant night at Cranemere, where our hosts were Eve Palmer’s nephew and his wife.

We drove to Durban in August 2001, choosing a scenic route that skirted Lesotho, on what was both sociologically and scenically a wonderful journey. On our circuitous route we passed the Great Fish River irrigation project in the Eastern Cape. I was not surprised to find that Bernard knew a great deal about this project – from his classes at Stretford Grammar School sixty years before. Despite having taken geography at Durban High School, I knew virtually nothing about what was South Africa’s major irrigation project. We then passed through Ciskei, the impoverished former homeland, where undertakers displaying their coffins with chilling regularity were a grim reminder of the toll being taken by Aids. Durban is my home town, but I have grown away from it; we were glad to see family and friends, but pleased that we had settled in the Cape rather than in Natal.

One of our trips was different and memorable: to celebrate Bernard’s seventy-fourth birthday, 13 May 2000, I hired a helicopter, and invited Eileen and her daughter Chris to join us for a flight over the Cape Peninsula. Starting at the Waterfront, we flew south along the Atlantic coast to Cape Point, then north along False Bay, circling our home.

Bernard, Pietermaeitzburg Botanical Gardens, July 2001 Bernard, Pietermaeitzburg Botanical Gardens, July 2001

Our young pilot told us that he had seldom seen such a clear day – we could see Langebaan, sixty miles to the north and Cape Agulhas, a hundred and ten miles to the east. Bernard, sitting next to the pilot in the front, took several rolls of film, and later meticulously put the best photographs into albums, all neatly labelled. That was the first time I had properly grasped the complex topography of the Cape Peninsula.

David Moir, Christine Moir (Bernard's neice) Bernard, DWB on Bernard's 75th birthday, 2001.

ENTERTAINMENT

We soon came to appreciate the variety and high quality of much that was on offer by way of live entertainment in Cape Town.

Angelo Gobbato, Professor of Opera at the University of Cape Town, has established a first-rate opera school, and has encouraged many young African and coloured singers, as well as sometimes recruiting singers from township church choirs. He has done a phenomenal job and many of his students have gone on to impressive professional careers.

At Artscape, the city’s largest theatre complex, and at other venues, staff were unfailingly helpful in giving us seats suitable for Bernard’s wheelchair. In the summer months, we went to open-air opera at Spier and at Oude Libertas, both located near Stellenbosch, and enjoyed some memorable and exciting performances. We often went with Elspeth and David Jack, because I did not enjoy driving that route at night. Cape Town’s Victorian City Hall offers excellent symphony concerts, with good acoustics, and we were happy to discover the Lindbergh Arts Centre in Muizenberg, a ten minute drive from Fish Hoek. The Lindbergh (which resembles a sedate club of

DWB, Bernard’s sister Eileen, Bernard. Two Oceans Restaurant, Cape Point, 2000

the 1930s) presents a morning and an evening concert each month, mostly singers or chamber musicians, often with young artists.

Another attractive arts feature is the annual Shakespeare play produced in the open air at Maynardville Park. We thoroughly enjoyed going to these plays, with a picnic by the lake with friends beforehand. Our local theatre, the Masque at Muizenberg, has also offered some compelling productions, and we were well served for movies in Cape Town, at the wheelchair-friendly Cinema Nouveau.

Bernard and I continued trying out new restaurants, concentrating on those in the winelands. Within our parameters, we found some outstanding restaurants. Durbanville Hills wine estate fully met our high standards, and as a bonus it was designed in a bold and imaginative way, architecturally one of the best venues we knew, and it was there that we had our last lunch, two days before Bernard died.

On coming to live in Fish Hoek we had been pleasantly surprised by the general cheerfulness with which we were greeted by people

DWB with members of Bernard’s family and friends on Table Mountain, 2001

of colour, any of whom, if they were adults, would certainly have experienced humiliation and discrimination, to varying degrees. Africans would greet me, Yebo, Mdala (‘Hello, old man’) and coloured men would say Môre, Oupa, all in an easy, friendly manner.

I am constantly struck by the poverty and the inequality which, I note with dismay, seems to be growing; there is an unsatisfactory record of delivery of services in many municipalities in the ‘new’ South Africa. I note too the devastation of HIV/Aids and wonder whether our Minister of Health will ever recognise that there is no substitute for antiretroviral drugs. There is much in the news about transformation and BEE (Black Economic Empowerment), and I am frequently reminded of California, and the struggles there over affirmative action, and opportunities for minorities. I am particularly interested in the role of ‘tradition’ – an elusive concept, and am often reminded of Ghana and Kenya where the governments also struggled to reconcile tradition and modernity.

PART 2 BERNARD’S LAST YEARS: 2001–2004

On 13 September 2001 (not coincidental, we believed, that this was two days after the harrowing ‘9/11’) Bernard had his first heart attack, from which he made a fairly good recovery, although after that his angina pains were more frequent and more severe. Then on 29 October, he had a stroke, while working at his computer.

That date, 29/10, was our worst turning point. Bernard had to be in a frail care centre, depressing because most patients had some form of dementia. I was worried because at first he hallucinated, telling me of visitors who did not exist, seeing flowers that were not there. During the first days, his left eye seemed to be out of focus; I asked if he could see me. ‘Yes,’ he replied, with an attempt at a grin, ‘wrinkles and all.’

Realising that we were in for a long and rocky road, I tried to educate myself about strokes, finding useful information on the Internet, especially ‘Ten Tips for Carers’, the most important one being: Be kind to yourself. When Bernard had been in frail care for a month, Father Bram told me that I must get him home, at once: ‘That place is no good for Bernard,’ he said, ‘and no good for you.’ I was fearful about whether I could cope at home, but Bram said, earnestly, ‘You will be given the strength, I promise you,’ and indeed I was – abundantly.

Once back home, Bernard’s progress accelerated, and we were both enormously relieved when it became clear that his mind had not been affected: his memory was excellent, his observations apt, his wit sparkling. We engaged Steina Daller, a nurse who came in every day (never on Sunday) until the end. She was brilliant: thoroughly reliable, knowing when to coax Bernard, compassionate, professional; she made both our lives much easier. Soon we developed a routine: when Steina arrived, at 7 a.m., I would go for my early morning fifty minute walk, the length of Fish Hoek beach, essential for my physical and mental well-being. Bernard encouraged me to continue going to the UCT seminars, appreciating that mental stimulation was important for me.

Bernard was left-handed and the stroke had affected his left side. One of his pleasures had been writing his letters and thoughts on trips and events; he had a rich descriptive gift, and a keen sense of humour, with an appreciative circle of friends who looked forward to his writings. After the stroke he could not use the computer. We tried a voice activator, which could not cope with Bernard’s slightly slurred speech. I took dictation a few times, but I could not persuade him to let me do this regularly.

Bernard and Steina Daller. August 2003

The last two years were frustrating for Bernard, as he became increasingly dependent on others. Despite this handicap, he was consistently cheerful and positive. What was remarkable was his ability to concentrate on those activities in which he could still engage and not to lament that he could no longer manage others. He told me that he felt sad because I did so much for him, while he could do so little for me. I reminded him that he had given me the greatest gift of all – he surrounded me with love: it was an exhilarating experience for me to return home and see his eyes light up, his smile broaden.

Physiotherapists helped Bernard’s recovery, starting from his time in the frail care centre. Ros, our first physiotherapist, helped him to walk again, even though at first he could manage only a few steps. She also helped him regain more use of his hand, with simple exercises. To improve his manual dexterity, Ros suggested that Bernard shell peas, but, alas, I found only canned or frozen, no fresh peas were to be had in Cape Town. Sadly, Bernard was never able to type again.

DWB and (favourite – and only – nephew) Garry. Fish Hoek beach, 2003

For nearly a year we went two or three times a week to an indoor heated swimming pool, where our new young physios, Leslie Abraham and Kerry, encouraged Bernard to do simple exercises, and to swim. I almost wept when I saw him painfully and slowly swim the ten metre length of the pool, remembering the days when he swam a mile daily, in half an hour. Bernard did all he could to help himself, and the physiotherapists remarked that he was a joy to work with, because of his resolve. In his last year, Bernard found the aquatherapy too tiring, so instead we went twice a week to Leslie at nearby Clovelly, where he put Bernard through a series of exercises to strengthen his left limbs. If Bernard was feeling too weak for the journey, Leslie would come to the house – he was a good-humoured and bright young man, whose visits were a tonic for Bernard.

MORE TRAVEL

We were determined to continue our trips, albeit on a less grand scale. Bernard had long hoped to visit Etosha National Park in northern Namibia. Geoff Duncan, our good GP, concerned lest Bernard suffer another heart attack when we were in the wilds, gave me morphine, together with a letter certifying that it was legitimate. I had never given an injection, so I practised, at Geoff’s suggestion, on an orange; fortunately I had no need to test my clinical skills on Bernard.

At first we considered driving, but settled, more realistically, on flying to Windhoek, then renting a car for the three hundred miles to Etosha. We stayed at a B&B in Windhoek, chosen because it advertised as being suitable for disabled visitors. The owner asked Bernard what additions to ‘our wheelchair-friendly room’ he would recommend. Bernard suggested a few improvements, and was delighted to find, when we returned a week later, that all his suggestions were in place. Would that all accommodation providers were so thoughtful!

Crossword time. Fish Hoek, 2003

We found Etosha a little disappointing – again we had such vivid, rich memories of the Kenyan parks in the 1970s, when the mammals and the birds were so much more abundant and varied. Even the vegetation had been more interesting. However, our trip was a useful exercise in confidence-building, showing us that there was still much that we could achieve.

On one of our last journeys along Route 62 in the Little Karoo, we stopped for the night at Ladismith. At about 10 p.m. – it was Sunday night – Bernard developed severe chest pains, and I asked our landlady for help. Within ten minutes a young Dutch doctor arrived, followed by an ambulance to take Bernard to the government hospital, where he had the usual tests. It was a ‘near’ heart attack; we were both impressed by the speed and quality of the medical attention that Bernard received in this small town.

|

|

| Celebrating DWB's 80th birthday at Chris and David Moir's home. May 2003 |

We spent a few days in the Cederberg, based in Clanwilliam, from where we visited the remote mission village of Wupperthal, navigating tortuous mountain roads. Bernard said that he was fully compensated by the remarkable geological structures along the way. From Clanwilliam we drove west to Lambert’s Bay with its huge colony of Cape gannets, now endangered by seals. Bernard still made good use of his camera, once again taking our Christmas card photograph.

Appelsdrift remained a frequent destination, and David Jack installed ramps so that Bernard had easy access to all the rooms; he also made the shower in ‘our’ room accessible. This Overberg farm was such a special place for Bernard and me. We were always warmly welcomed by the Jacks, their staff, and even the dogs.

Once, when we were driving in Cape Town I told Bernard that we would be turning into Milton Street. Not sure if he had heard me, I said, ‘You know, as in John Milton.’ Whereupon Bernard recited On His Blindness, perfectly:

When I consider how my light is spent …. … God does not need

Either man’s work or his own gifts, who best

Bear his milde yoke, they serve him best …

They also serve who only stand and waite.

It was indescribably poignant. Bernard then told me about his fourth form English master, who had encouraged him to memorise this – and many other poems – in about 1941.

Bernard liked to go out every day, unless he was particularly in pain, or tired. A little outing would suffice, perhaps for coffee at Simonstown Jubilee Square, though sometimes we went further afield. We continued our tradition of wineland lunches, revisiting our favourite places, and discovering new ones. It was always a pleasure for me, taking Bernard out, not just because of the good food and wine and scenery, but also because he was so keenly observant of physical and social phenomena. After lunch, for which Bernard always dressed elegantly, he would rest happily on the bed, content to observe the view and drowse until it was time for our sundowners.

One side benefit was that my cooking improved dramatically. For all the years that we had been together, even after his cardiac problems, Bernard had taken care of most of the domestic routine, including the cooking. After his stroke I was on a steep learning curve, much helped by two publications: Mary Berry’s Complete Cookbook was a godsend, and Weber Cooking: South African style was invaluable when I used the braai. Bernard constantly encouraged me, amazed at my new-found skills.

In his last period, Bernard read little. He did not have the energy for newspapers, but eagerly seized the weekly New Scientist, and read it from cover to cover. He no longer did crosswords, and he read chapters rather than whole books. Sometimes he simply lay on the bed, resting, and if I asked whether he was alright, he would smile and say, ‘Just thinking, and remembering … I’m quite alright.’

Bernard insisted, whenever he could manage, on going to mass, usually to the Saturday evening service. At first he could manage with the help of a walker, but later he had to depend on his wheelchair. He would often weep with joy after receiving communion.

The last photograph of Bernard. Kleine Zalze winery, near Stellenbosch, November 2003.

In 2003, Bernard’s niece, Chris Moir, invited us, as she had each year, to join them for Christmas Day lunch. I was not sure if Bernard could manage this, as he was noticeably weakening, but he was adamant: ‘the children will be disappointed’ and, with a great effort of will, he went, thoroughly enjoying the lunch and the company. He was exhausted when we came home, but we all admired his courage and determination. Bernard was battling on three fronts: his cardiac problems, the effects of his stroke, plus prostate cancer, diagnosed soon after his stroke, which had not responded to radiotherapy, hormonal treatment nor chemotherapy.

In the evenings Bernard was usually in bed, asleep, by 8 p.m. I would read or potter until about 10 p.m. When I joined him, Bernard would rouse and say, ‘Here’s my little blue-eyed boy,’ purr like a cat, cuddle me, and fall asleep. I thought that that was a silly thing to say to a little old man, but after he was gone I would have given anything to hear him say those sweet words again.

A GOOD EXIT – NOTES FROM MY DIARY

Saturday 17 January

Bernard was in pain, from the prostate cancer, and Dr Duncan prescribed morphine, to be taken orally every four hours.

I went to morning mass and brought communion for Bernard. He felt well enough to go out to lunch, to celebrate our forty-nine and a half years together – we realised that it was unlikely that he would be here on July 17th for our fiftieth. We had crayfish at the Victoria & Alfred Hotel at the Waterfront. Bernard’s spirit was high.

Tuesday 20 January

Bernard had his last (of five) radio-therapy treatments, and saw Dr David Eedes, our oncologist, who was concerned about his weakness.

Wednesday 21 January

Realising that time was short, we drove to Bernard’s favourite venue, Durbanville Hills winery, where we had an excellent lunch, and a bottle of very special Biesjes Craal Sauvignon Blanc, while looking across to Table Mountain from the north.

Our caring parish priest, Father Bram, gave Bernard the Sacrament of the Sick at 5 p.m., then the three of us had a whisky sundowner. Bernard and I thought that we would go and see the movie Peter Pan the next day.

Thursday 22 January

Bernard had severe chest pains. Dr Duncan came at 7 a.m., diagnosed another heart attack and gave Bernard a morphine injection, telling me that I should be ‘prepared for anything, at any time’. Because we had made Living Wills, Dr D (who visited three more times in the next twenty-four hours) did not send Bernard to hospital, knowing that we both wished him to stay at home with me until the end.

When I asked Bernard at noon if he would like a Pernod (his favourite tipple), he smiled weakly and said ‘Silly question’ – although he did not finish his drink. With all the morphine, he was drowsy, though lucid at intervals. When I knelt by his bed, he held my hand, and said, ‘Oh, I do love you so much.’ Our nurse, Steina, who had been with us all day, stayed all night, so that I would not be alone.

Friday 23 January

Chris arrived at 9 a.m. As Bernard’s breathing was so laboured, I called our Home Nursing Services at 11 a.m., and Sister Martin came immediately. She made Bernard comfortable, stayed a little while, then, as she was packing her medical bag, Bernard roused and said, clearly, ‘Goodbye, Sister … good-bye.’ As he was looking at us all, we are sure that this farewell was meant for the three of us. Then Bernard turned on his side, and a minute later Sister M felt his pulse and said, ‘He’s gone.’

DWB completing 10 kilometres of Cape Town’s annual Big Walk. 2005

Tuesday 27 January

Father Bram conducted a moving funeral service, during which he said: ‘Bernard and David had such a great love for each other, it should be an example for us all.’ What comforting words. We had a celebration afterwards of Bernard’s life. I had thought of offering tea, but David Jack provided good Flagstone wine, correctly pointing out that Bernard would prefer us to drink wine to remember him. He had a good send-off.

After the funeral, Pete Sievwright phoned, not to ask me what I needed, but to tell me that he would be coming shortly to collect me and take me out to dinner. What a star, as we say in South Africa. I was in no state to make decisions, and we had a good evening, I wept a little, and I was much comforted by the dinner and by our conversation.

During his last weeks, Bernard and I talked about his death. At his wish, we had bought two plots for our ashes in our church’s ‘Garden of Remembrance’. A few days after Bernard’s death, Bram and I placed his ashes in the Garden of Remembrance.

PART 3 SANS TOI: JANUARY 2004–2007

Bernard and I had discussed his death, which both of us recognised was approaching; he would seriously ask how I would manage, ‘sans moi’. Sometimes he would say, tearfully, ‘I don’t mind dying but I don’t want to leave you.’ He also urged me: ‘Get on with your life when I’m gone; don’t mope.’

No matter how prepared we are for death, its finality is always a shock and I had a difficult initial adjustment. My head told me that Bernard and I had been so lucky in having had all those years together, and also because he had retained his mental faculties to the end, and had not suffered greatly. But my stubborn heart ached: I missed him dreadfully.

In this first bleak period I was helped immeasurably by our friends, those who telephoned, emailed, or wrote letters, and those who lived in the Cape. Our friend Enid Bates, whose husband Howie had died eighteen months previously, was a constant source of encouragement. Enid became a good companion to me, accompanying me to theatres and concerts and on small outings in the country. Elspeth and David Jack made me welcome at what I call their ‘magical farm’, where I spent several days after the funeral,

CLOCKWISE FROM TOP LEFT: DWB’s great-nephews, Deirdre’s sons: (from left) Philip, Patrick, Steven and David at Patrick’s wedding, 1996 Niece Deirdre with her husband Peter Blackwood. Caithness, September 2006 Niece Lindsay LeesMay. Mukwazi ranch, Zimbabwe, 1991 Niece Judy Homan on her sixtieth birthday. Umhlanga, September 2007

walking with the dogs in the Overberg hills, and getting myself together. I go there for a few days every month, much enjoying both the grand scenery and the stimulating conversations – I have made so many new friends at that hospitable refuge.

Bernard’s niece, Chris, and her family keep an unobtrusive caring eye on me, as does Pete Sievwright, who invited me to accompany him, in early 2004, to Zimbabwe and Zambia, where I was able to see my niece Lindsay on the lower Zambezi River, and my sister-inlaw Lizzie Brokensha in Bulawayo. This trip was important, proving to me that I could travel alone. In fact I did not feel alone because so many of the places I had first visited with Bernard and I could feel his loving presence with me.

Later in that first year, Lanys Kaye-Eddie invited me to join her at a Grand Horse Auction near São Paulo, Brazil. I stayed on for two weeks as a tourist in Brazil, again testing to show myself that I was ‘alright’ as a lone traveller. I enjoyed that trip enormously.

As well as having support from our many friends, I was helped by a little book that Bill Northrup (whom I had met at the University

DWB in the Pantanal. Brazil, 2004

of Ghana in 1963) sent me: Martha Hickmore Whitman’s Healing after Loss: Daily Meditations for Working Through Grief. Europeans mock Americans and their self-help books, many of which, I admit, are trite and sentimental, but this book is different, comprising a collection of carefully selected readings, with commentaries by the author, whose sixteen-year-old daughter had died in a riding accident. I read the daily readings for a year, frequently concluding that they could have been tailored especially for me. During that period, I wrote to Martha Whitman and we had a good exchange of correspondence.

At the suggestion of my godson Adam Lister, I planted a tree (an African olive, Olea africana) in Bernard’s memory, at Appelsdrift farm; Father Bram came out to bless Bernard’s tree and the other memorial trees that we planted.

I now regularly attend the Wednesday morning mass in Simonstown ‘for our departed sisters and brothers’, finding solace in that, and comfort when widowed parishioners ask me how I am doing, saying that they know what it is like, the ups and downs. They allowed me to feel that my grief was legitimate.

Some ‘ex-Catholics’ would be amazed, even horrified, that Bernard and I stuck with the Church, but I have never thought of leaving: I am a Catholic, I shall die a Catholic. Once when talking to Father Michael in Sherborne, I voiced my difficulties with Rome and the conservative Curia. He advised me not to worry about Rome, but to think of our parish as the Church. This is the experience of many Catholics. Even the Australian writer David Marr, a fierce critic of the Catholic Church, wrote in his book The High Price of Heaven, ‘as always in the Catholic Church, there’s a schism between dogma and what’s really happening on the ground.’

Father Bram Martijn. Appelsdrift, 2004

So, thanks to my dear friends, I took up the strands of my life with travel, shows, attending anthropology seminars at UCT, walking and writing. I continued writing my periodic Fish Hoek Notes, a circular letter for friends. I wrote a memoir of Bernard, which my computer friend Donald Gill put onto a website for me. This was excellent therapy for me, describing Bernard’s life and re-living the happy fulfilling years that we spent together. I have also been writing this book, which has provided a useful focus for my days, and a good discipline so that I do not simply potter my hours away – so easy to do as one gets older.

When I met Bernard in 1954, he and I had different temperaments. He was organised and tidy, and had what I called a ‘siege mentality’: food and clothing had been in short supply during his wartime teenage years in Manchester. I, on the other hand, tended to be rather careless with possessions. I was happy to follow Bernard’s

Nigel Morris (niece Robin’s husband) and DWB. Isandlwana, February 2006

CLOCKWISE FROM TOP LEFT Tom Searles and John Burton. Erina, NSW, Australia Cousins Peter and Elizabeth Brokensha. Kangaroo Island, South Australia Pat Griffith. Carpinteria, California Ann and Manuel Carlos. Watsonville, California Molly and Ted Scudder. Altadena, California

instructions regarding the folding of socks, the hanging of shirts, the tying of shoe-laces and a hundred and one other domestic details, particularly regarding the kitchen, where his skills were much more developed than mine. Another difference was that, whereas Bernard was cautious in his initial interactions with strangers, I was more open, and was sometimes too trusting.

Our interests and preferences in the arts – in opera and concerts, paintings, movies and literature – overlapped considerably, if not entirely.

CLOCKWISE FROM TOP LEFT Kim Lake. Oxford Monica and Michael Turner. Salisbury Josette and Cees Post. London Pat and Paul Baxter. Lancashire The photographs of friends and family on these two pages were taken during DWB’s round-the-world trip in 2006.

TOP: DWB, great-grandnephew Samuel, great-niece Tracey Wilson (daughter of Bernard’s niece Felicity). KwaZulu-Natal, February 2006 ABOVE: Celebrating DWB’s 84th birthday: sister-in-law Lizzie, Martin West and DWB Photo: Martin West

We shaped each other, Bernard became more relaxed and I acquired a better sense of order. Bernard made me more observant of the physical environment and I heightened his sensitivities about people. I could not have wished for a better companion on my life’s journey.

It was through our love for each other that I became comfortable with being gay. When we first met, homosexuality was illegal in all the countries where we lived. There were gradual changes: the 1967 Wolfenden Report led to the decriminalisation of homosexuality in Britain in 1969. That same year saw the Stonewall riots in New York and the beginnings of Gay Liberation. In 1973, the American Psychological Association removed homosexuality from its list of psychological disorders. And finally, when we moved to South Africa in 1999, for the first time we were in a country whose constitutional rights included sexual identity. It was a thrill for me to be able to discuss the legal position of gay men with Albie Sachs, a judge of the South African Constitutional Court.

What will I do next? With the help of my colleague Ted Scudder, I am planning to write a history of our Institute for Development Anthropology, which will also examine international development during the last quarter of the twentieth century. I would also like to try to learn some Xhosa.

I also have more travel plans, encouraged by a three month round-the-world trip that I made in late 2006, to see friends and family in the UK, the USA and Australia: it was a wonderful experience, because of the welcome given me by our friends.

As happened during his lifetime, I still try to make Bernard proud of me; it is a powerful and a beneficial sanction.

|

next part

| |

|

|