|

|

|

|

|

|

|

1940–1942:

WORLD WAR 2 – DISPATCH RIDERS 1940–1942:

WORLD WAR 2 – DISPATCH RIDERS

Britain declared war on Germany and Italy on 3 September 1939. General Jan Christiaan

Smuts, Prime Minister of South Africa, declared

war three days later. I remember cycling to school

from our home in Heron Road, eagerly speculating

with Alastair Dark how the war (which was how we referred to World War 2, then and later) would affect our

lives: we had little inkling of how drastically

they would be disrupted.

Many members of the opposition National Party were against South Africa’s

participation in the war, some being fanatically

pro-Nazi. One of the most extreme was Oswald Pirow,

who resigned as Minister of Justice in order to

support Hitler. All of us in the forces loathed

Pirow, and it still galls me when I drive along

a major road in Cape Town named after this infamous

man.

Given the divided opinions about the war, Smuts declared that there would be

no conscription, and soldiers would not be required to serve outside South Africa unless they chose explicitly to do so.

These volunteers were identified by orange shoulder

tabs, which were worn with pride.

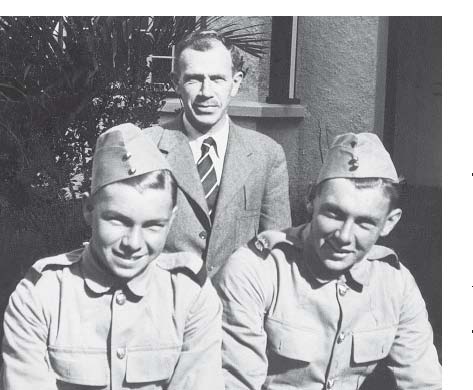

Guy

in the Fleet Air Arm. 1940

In July 1940 Paul and I were both home for the vacation, I from Rhodes and Paul

from his last year at Maritzburg College. We wanted

to get involved in war, partly from patriotism,

partly from what we saw as the adventure and glamour,

and partly because neither Paul nor I was content

in our respective institutions. Paul was impatient

to be away from the restrictions of school, and

I was too immature to be taking advantage of my

time at university. Influenced by Guy, who was already

a decorated pilot in the Fleet Air Arm, we aimed

to join the South African Air Force. Guy was an

irresistible model and hero to his impressionable

younger brothers.

Dad was then in Addington Hospital, recovering from abdominal surgery. It was

not a matter of asking his permission, because we

had been brought up to make our own decisions and

Dad knew that nothing would stop us from joining

up. I had a twinge of guilt because Dad looked so

frail, but he gave us his blessing, asking only

that we stay together so that we would be able to

look after each other: ‘I shall worry about

you boys, of course, but I shall worry much less

if I know that the two of you are together.’

Paul and I readily accepted this stipulation, because we got on well despite

our different interests. During the following five

years we were frequently grateful to Dad for this

request. We found that the worst parts of the war

were made tolerable by the close fraternal support that we developed: only after Paul’s

death, in 1986, did I fully appreciate how close

a bond we had forged.

DWB,

Dad and Paul. Durban, 1941

In our careless, youthful way we thought little of the feelings of our parents,

who did not impose their anxieties upon us. Dad

remarked to a friend at the Durban Club that he

was concerned, because all three of his sons were

serving in the forces. His friend replied that he

was even more concerned, as not one of his three

sons showed any signs of wanting to join up. Dad

told us that he felt very proud of us.

Paul and I had hoped to join the South African Air Force and be trained as fighter

pilots, but we met an obstacle: the minimum enlistment

age was eighteen and a half and I was only seventeen

years and two months. Paul, being eighteen months

older, would have been accepted but we were committed

to staying together. We could have waited until

November 1941, when I would have reached the requisite

age, but we were afraid that, by the time we finished

our pilot training, the war might be over.

While Paul and I were walking on the Esplanade, considering various alternatives,

we paused at an army recruiting office with an improbable,

exciting poster calling for volunteers for the cavalry.

The poster depicted a gallant young horseman galloping

on a sturdy steed while dodging enemy fire. Cavalry?

In 1940? While pondering this we were hailed by

Aubrey Davies, whom we knew from sailing, who was

a member of the recruiting staff. He told us to

ignore the cavalry poster and said that he could

offer us a much more exciting option – as

dispatch riders. ‘How would you like to ride

Harley-Davidson motorcycles?’ We were won

over at once, and followed Aubrey inside the office

to fill in the forms. Fearful of being rejected

again, I put the date of my birth back a year, making

it 23 May 1922 (instead of 1923). The recruiting

sergeant drily remarked we had a clever mother as

the age difference on our forms showed an interval

of only six months, but he cheerfully admitted us

to the Second South African Division Signal Company,

allocating us our army numbers, 3738 for me, 3739

for Paul.

JULY 1940 TO MAY 1941: POTCHEFSTROOM

Paul and I spent a few weeks in Durban, where I learned to ride a motorcycle

(Paul at 18 could already do everything), not

the promised Harley-Davidson but a more manageable

BSA 350. We then went to a large army camp at

Potchefstroom (always referred to as Potch), a

hundred miles south-west of Johannesburg. My first

few weeks there were a shock. Like millions of

others throughout history I had to adapt, quickly,

to vastly different circumstances and to different

sorts of people. I was embarrassed by the toilets,

which offered no privacy, being in long rows where

squatters chatted companionably to their neighbours.

Paul was prepared for this, both by his experiences

of boarding school, and also by his more robust

temperament. I would get up at about 4 a.m. to

avoid the embarrassment of sharing this hitherto

private office. At one early-morning session I

was joined by Bill Payn, a popular teacher at

Durban High School, who had joined the army despite

being forty years old. Mr Payn jollied me out

of my discomfort, saying, ‘Dave, everyone

has to shit, and this is the way we do it in the

army. You will get used to it.’ Although

I never really got used to it, it did become less

upsetting.

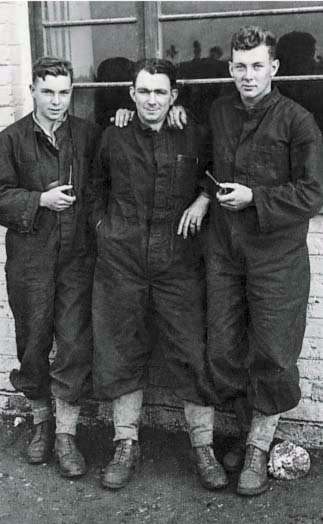

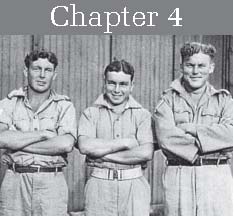

What was more important to me were my new friendships, the most significant being

with Ernest (Jake) Jacobsen. Jake’s parents

had recently died and Ouma informally adopted

him, inviting him home whenever we went on leave

to Durban and treating him like her own son, and

he became like a brother to Paul and me. We were

all ‘Don Rs’ ( dispatch riders), and

considered ourselves superior to the radio operators,

the motor transport and the other sections of our signals unit. This attitude of superiority

was unwarranted for it was the radio operators

who did the most effective work. We may have added

some glamour to our unit but I have no clear idea

of what contribution we, as dispatch riders, made

to the course of the war.

Jake. Potchefstroom, 1941

Another significant new friend was Leslie Rubin, an attorney in Durban. Many

years later, when I asked what he recalled, Leslie

wrote to me:

I remember the day, not long after I had joined up, when [your father] whom I

knew well as a senior colleague – Brokensha

and Higgs was one of the older legal firms in

Durban – came up to me as I was on my way

to court, and said he had heard I was with the

Second Division Signal Company. ‘My two

boys are in the same unit and I would appreciate

it if you would keep an eye on them.’ I

sought out Paul and David as soon as we got to

Potch and saw them from time to time thereafter,

the last time being after we had gone to North

Africa, at Amiriya. The vivid picture that remains

with me is of their being almost inseparable,

Paul a most conscientious, devoted and protective

older brother and David very shy and usually looking

serious and thoughtful, with very blue eyes.

(Leslie was later made an information officer, stationed in Cairo. After the

war he was vice-chairman of the Liberal Party,

and a senator representing Africans in Parliament;

we met again in 1960 when he was Professor of

Law at the University of Ghana. We later met both

in California and in the Cape.)

Other new friends included several young Afrikaners. I cringe now when I think

how superior, with no justification, we English-speaking

Natalians felt, regarding Afrikaners. (The population

of South Africa in 1940 was about 11 million,

including 2.3 million whites – ‘Europeans’

– of whom about half were Afrikaners.)

A disproportionate number of Afrikaners joined the army, partly because of their

relative poverty: the depression of the 1930s

had caused many Afrikaner bywoners (those who squatted on farms, having no land of their own) to leave the farms

and migrate to the towns. My closest Afrikaner

pal was ‘Piet’ Pieterse, who came

from a poor background and had recently spent

time at a reformatory for juvenile offenders.

Despite our differences, we had a close and affectionate

relationship. My heart always gladdened when I

saw Piet’s gap-toothed grin; he would embrace

me, calling me Dawie, or my klein dafodel, and laugh uproariously. Piet was killed at Tobruk two years later, our first

fatality.

I had a few other such close friendships, which resembled what the Australians

call mateship, a relationship between two soldiers with intense affection and occasional homoerotic

undertones (Billany, 1952). Such mates would be

emotionally extremely close, and mutually dependent.

DWB,Ted

Harris, Paul.Potchefstroom 1940 ake. Potchefstroom,

1941

Other memories are less happy. Once, I ordered the driver of a bakkie (a pick-up truck) to move away from the road, to allow the convoy to pass. A

woman sitting in the open back of the truck spat

at me. I did not pay much attention; in any event

we wore full face leather masks to protect our

faces from the stones which were thrown up. But

Bennie Burke, one of my fellow dispatch riders,

was furious at this insult to me and, taking out

his revolver, forced the passengers, all Afrikaners,

to get out of the truck and stand with their hands

up until the convoy had passed. What the woman

had

Dispatch riders. Potchefstroom, 1941 Middle row from left: 5th Dickie, 6th Paul, 3rd from end DWB, end Jake

done was not surprising, for in that part of the country there was much anti-army

and even pro-Nazi sentiment: many had bitter memories

of the Anglo-Boer War of 1899–1902. I recall

this incident with mixed feelings because it probably

only increased the woman’s antipathy.

A surviving letter from me to my parents, headed ‘Potchefstroom Aerodrome,

November 13th, 1940’, says: ‘The DonR’s are not neglected. Yesterday we went out for practical

map reading and were invited in for tea, all seventeen

of us, by an Afrikaner farmer.’ So

not all Afrikaners felt the same way.

One of our instructors was an old (probably about forty years old) Afrikaner

regular army sergeant major who gave us excellent

advice on the maintenance of our motorcycles,

and the tracing of faults in an internal combustion

engine. His advice stood me in good stead many

years later, when I did the maintenance of my

own Land Rover in the bush in Tanganyika. He amused

us by recommending that we take a bacalav (a balaclava helmet) to the desert, because the nights would be cold; later

we were grateful for his advice. He also told

us that we should carry a bar of Sunlight soap

so that when the enemy fired into our petrol tank

we could repair the holes with the soap. Our motorcycles

were never fired on by the enemy, but in 1956,

when Bernard and I were driving our old 1939 Chevy

in Rhodesia, from Bulawayo to Maleme Mission,

we bumped on a stony ridge, rupturing the petrol

tank. In the pouring rain we found soap and plugged

the leaking tank, gratefully remembering the old

sergeant major.

When we had weekend leave, from 1200 hours Saturday until 2359 hours Sunday,

we liked to go to Johannesburg, which was two

hours away by train. I recall with pleasure being

invited to homes where there were soft beds with

clean linen, privacy, nicely prepared and properly

served meals and all the other little luxuries

that we had taken for granted before we joined

the army.

Potchefstroom was the home of one of the major Afrikaans universities, where

many of the students and staff were vociferously

anti-British and pro-German, causing tension and hostility in relations between

the army camp and the university. When the Union

of South Africa was formed in 1910 – from

two British colonies and two formerly independent

Afrikaner republics – English and Afrikaans

were both declared official languages, and the

new nation had two national anthems, the familiar

God Save the King and the new Die Stem van Suid-Afrika: ‘The Call of South Africa’. Troops were allowed leave to go into

the town, where, at the end of a film at the local

cinema, the two national anthems would be played.

Everybody stood up for Die Stem, but when God Save the King followed, some students would try to push their way out. This resulted in farcical

scenes, with soldiers steadfastly standing to

attention and ignoring the blows until the last

note of God Save the King was sounded, after which there would be a free-for-all fight.

The troops would return from weekend leave in Johannesburg on the last train,

alighting at a small siding, a mile from our camp.

One night one of the stragglers, a small and mild

and popular man, was found with a broken leg,

having been attacked by a group of townspeople.

In retaliation, an angry mob of soldiers invaded

the university, thrashing all the students they

could find. (Neither Paul nor I took part in this

reprisal raid.) My fellow soldiers boasted that

they had found a grand piano, played God Save the King, forced the students to stand to attention and then thrown the piano over a

balustrade. They had also spilled books in the

library, which sickened me: it was too similar

to what Hitler’s thugs were doing in Germany.

This was not my scene.

A happier memory is of army manoeuvres. In Bechuanaland Protectorate (now Botswana)

we had great opportunities to ride our Harley-Davidsons

along bush and desert tracks, camping out at night

and having mock battles. Later we went to the

eastern Transvaal, near Barberton, and on one

occasion mechanical trouble delayed me. Trying

to catch up with the convoy, I took a short cut

along a remote dirt road, but I rode too fast

and was thrown off my machine. I realised that

I had broken something (it proved to be

DWB. Durban, 1941

my collarbone) and I had a bad time, in pain, on this lonely road, until I was

rescued by an Afrikaner farmer who put me and

my Harley-Davidson on his truck, and took me to

rejoin the others. As soon as the bone had healed,

I got on my Harley-Davidson again, determined

to prove that I was not afraid.

MAY/JUNE 1941: ORIBI CAMP, PIETERMARITZBURG

After nearly one year at Potch, we spent six weeks at Oribi, in Pietermaritzburg,

a staging camp for troops waiting to go ‘up

north’. At Potch we had been accommodated

in barracks, but at Oribi we slept in bell tents,

eight men to a tent. Pietermaritzburg is bitterly

cold in winter, so this was not a comfortable

period. We were granted leave generously though,

and were often able to hitchhike the fifty miles

to our home in Durban.

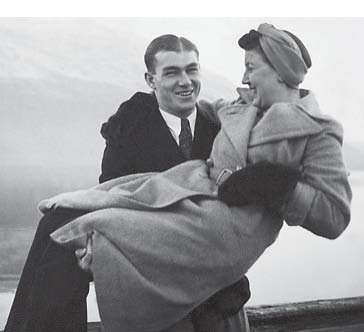

We liked to go dancing at the Blue Lagoon, a popular and genteel night-club where

Paul could take his girlfriend Jil, whom he married

after the war. My partner was Shirley May, who

lived near us and whom I had known for many years.

She was good company, but, looking back, I can

now see that I was never seriously interested

in girls.

Dad allowed Paul to borrow his car and, one evening, driving home after dropping

off the girls, we picked up a British soldier

who asked if we could take him to a brothel. Paul,

ever enterprising, found a man who agreed to be

our guide, taking us to a modest house near the

Durban Botanic Gardens. What stays in my memory

is the aplomb with which Paul handled the whole situation as we accompanied our

new friend inside – only for a beer, not

for the real business of the evening. It was,

literally, my first multiracial party: the ladies

of the house represented all South Africa’s

racial groups and were all marvellously at ease

with each other and with their waiting male customers,

a cross-section of our gallant allies. An evening

to be remembered. After many false alarms and after being told – accurately – via German

radio, that we would be sailing on the Ile de France (a luxury liner converted to a troopship), we embarked for Suez, and spent the

following year in north Africa.

Dad allowed Paul to borrow his car and, one evening, driving home after dropping

off the girls, we picked up a British soldier

who asked if we could take him to a brothel. Paul,

ever enterprising, found a man who agreed to be

our guide, taking us to a modest house near the

Durban Botanic Gardens. What stays in my memory

is the aplomb with which Paul handled the whole situation as we accompanied our

new friend inside – only for a beer, not

for the real business of the evening. It was,

literally, my first multiracial party: the ladies

of the house represented all South Africa’s

racial groups and were all marvellously at ease

with each other and with their waiting male customers,

a cross-section of our gallant allies. An evening

to be remembered. After many false alarms and after being told – accurately – via German

radio, that we would be sailing on the Ile de France (a luxury liner converted to a troopship), we embarked for Suez, and spent the

following year in north Africa.

Paul.

Durban, 1941

JUNE 1941 TO JUNE 1942: THE WESTERN DESERT

Army life in north Africa was not particularly stressful. It became increasingly

clear that we dispatch riders were hardly an essential

part of the plan for victory, but we had many

opportunities to enjoy ourselves. We were camped

first at Mersa Matruh, two hundred miles west

of Alexandria, then we moved a further two hundred

and fifty miles west, to camp on the outskirts

of Tobruk (now Tubruq). The only civilians we

glimpsed – and that very occasionally –

were small bands of nomadic Bedouin Arabs.

Despite the terrible disadvantages, the desert had charm, almost a fascination,

which affected most of those who lived and fought

there. The vast distances, the deep silences,

the tricks of light, even the spartan conditions

had a profound effect on the soldiers who were

in this desolate wilderness … Because there

were so few civilians, and thus few distractions,

the armies … became such closely knit organisations

that the word family best describes them. The

Desert and its ways produced, in addition to peculiar

ideas of dress, the invisible but distinctive

styles of companionship, loyalty and decency which

were never found in any other theatre of operation.

(Lucas, 1978: 28) During the war, General Smuts’ wife, universally known as Ouma (Granny), took a special interest in the welfare of the South African troops:

‘my boys’, she called us. She insisted

that all South African troops on active service

outside South Africa should receive a daily tot

of brandy, and two hundred cigarettes every week.

In those days nearly all of us smoked, and nearly

all of us enjoyed the brandy: we saved the tots

until we had free time and could have a party.

There were no health warnings about Commando Brandy

and Springbok cigarettes. Paul, by then our platoon

sergeant, and I shared quarters, usually dugouts,

which we made comfortable. We even had the luxury

of a real bath tub, which we had found abandoned

in the desert. With wells nearby, water was not

a problem. Dad later told us that when he met

our general at the Durban Club he asked, ‘I

don’t suppose you would have encountered

my two boys?’ and the general replied, ‘Indeed

I have; I used to envy them enjoying their bath,

when all I had was a canvas basin.’

.

Top:

Ouma Smuts, Pietermaritzburg. 1940.Photo: Ouma

Brokensha

Above:

Jimmy Daniel, Alexandria, March 1942

NORTH AFRICA

Another pair of brothers, preparing their dugout, found a plague of sand fleas.

To eliminate them, they poured what they thought

was paraffin over the sand walls and set it alight:

the fuel proved to be petrol, and one brother

was critically burned. This was a sad reminder

that in any war a high proportion of casualties

result from accidents.

At this time I had a new mate, Jimmy Daniel. He was my age, with an exuberant

personality, and was a great companion. He had

been a mechanic at Kempster Sedgwick garage before

the war and was in MT (motor transport). We became

close friends and I often spent the night, with

Paul’s permission, in the enormous cave

where the MT unit had established themselves.

It was cold in the desert at night and Jimmy and

I would cuddle up to sleep; I heard one of our

friends say, with no hint of criticism, ‘Look

at Jimmy and Dave, sleeping like two puppies.’

Jimmy joined our group when we went on leave to Alexandria – we liked doing

everything together. Although we did not end up

in

DWB on his Harley-Davidson (note socks drying). Western Desert, 1941/2

the same prisoner of war camp, after the war he asked me to be godfather to his

first-born son, whom he called Warwick, after

my middle name. Sadly I lost touch with Jimmy

many years ago. Paul was much better than I at

keeping in touch with our wartime pals, but I

was having my own battles trying to settle down

at university, and sorting out my sexual identity,

and then I left South Africa.

On one occasion I was sent out with dispatches to a contingent about fifty miles

south in the Qattara Depression. I set off on

my Harley-Davidson but soon became lost –

easy to do in that trackless desert – and

in any case I do not have a good sense of direction.

I was eventually found by a group of New Zealanders,

who took me in for the night as it was too late

to return to base. I asked them to send a message

to my camp but this did not get through and, later

that night Paul, worried by my absence, woke up

the general and had him organise a wide search

for me. When I returned to camp the next day,

I was embarrassed to have been the centre of so

much attention, but also overcome with love for

Paul, when I realised how very concerned he had

been. We rarely articulated our emotions.

Towards the end of our stay in the desert there was a serious shortage of spare

parts for our Harley-Davidsons. An expensive machine

might be abandoned because a simple piston ring

was not available – a dramatic lesson for

me in the importance of maintenance. (Much later,

studying development in Africa, I encountered

many instances of failure of elaborate development

projects – water, roads, irrigation, transport

– for lack of adequate maintenance.) We

relied more and more on Dodge and Chevrolet trucks,

but even with these there was often a problem

finding spare parts. We formed a gang composed

of both dispatch riders and MT people, the aim

being to steal (we preferred scrounge) vehicles from other units, in order to keep mobile. While I am ashamed of some

of my wartime activities, I have no regrets about

our gang, it was all for the common good. The

captain in charge of MT (who, after the war, asked

Paul for a reference for a job as a car salesman)

turned a blind eye to our activities, gratefully

signing the forms we presented.

The genius behind our gang was an unimpressive, slight, shy man, Doug Lonsdale,

a clerk in MT, who converted our stolen vehicles

into apparently legitimately acquired trucks and

motorcycles. This entailed giving them new registration

numbers and ensuring that the records tallied

with the stock of always-changing vehicles. One

night we struck gold in Alexandria, finding not

only an unattended one ton truck but also two

motorcycles, all standing outside the Officers’

Club. We fortunately had a three ton truck, into

which we loaded the motorcycles while one of us

sped away with the one ton truck. In the back

of the three ton truck, Doug told us which numbers

to put on our new vehicles. It was all very exciting.

Once I found a BMW motorcycle, the best machine that I had ever ridden, abandoned

in the shifting battles that were taking place

around us. Near Tobruk was a fine stretch of brand

new tarred road along which I tried it out –

it was wunderbar. Then I noticed, riding at great speed towards me, another young man dressed

as I was – clad only in shorts. As we got

nearer each other, something indicated that he

was not one of our boys, that he was German. The

same realisation must have come to him, for we

both turned abruptly around, giving each other

a friendly wave, and raced back to our respective

bases. ‘One of the most important requirements

in the African campaign was the ability to identify

quickly and at long range men or vehicles encountered

in the desert’ (Lucas, 1978:

22We were never far from the coast and were often able to swim in the sea. Paul

and I taught many up-country boys how to swim,

the Mediterranean being an ideal learning environment.

We were not over-busy; I remember halcyon days

on the beaches, swimming, wrestling, talking,

dreaming, playing jukskei. (Jukskei is a South African DWB and Paul. Tobruk, 1942 game, similar to the American ‘horse-shoes’, played originally with

jukskeie or yoke-pins.) We fashioned rough pegs to serve as jukskeis. Even in winter when the Mediterranean could be chilly, we swam whenever we

had the opportunity. While on the beach we were

naked, and when I recall those scenes, we seem

like figures on a Greek vase..

DWB

and Paul, Tobruk, 1942

We had leave about every six weeks when we could go (usually by train, sometimes

by road if any of our transport was going) to

Alexandria or, less often, to Cairo. Looking back

at our two or three day leaves I am struck by

what a callow youth I must have been. Many other

young soldiers (Bernard especially) used their

wartime leave to good advantage, to explore sites

of cultural and historical interest, and to meet

local people. Now I realise how much more there

was that I could have done. But we always went

in our little group of five, with Paul inevitably

the leader. We did see the pyramids, and wander

around a few markets, and we saw, with little

understanding, a few ancient buildings. But I

do not regret the luxury of ice-cream or cake

or iced coffee at Groppi’s, the famous Alexandria

café: what a joy after the usually gritty

and dull meals in the desert. I should say though,

in fairness to our army cooks, that they could

produce tasty meals under difficult circumstances:

I remember particularly their delicious bully

beef frikkadels (rissoles).

Returning from one of our leaves in Alexandria, on a late train packed with mostly

drunken troops from different countries, I became

separated from Paul, and an Australian threatened

me, with no provocation. I wondered if my last

day had come when this huge man swung at me in

the crowded train corridor, but he did not connect,

as his mates held him and the liquor slowed his

reflexes. Suddenly, in a sequence that could have

come from a movie, reinforcements arrived in the

shape of our little gang led by Paul. Then there

was a general mêlée, Australia versus

South Africa, with me, the unwitting cause of

it all, sheltering in a corner. No great harm

was done, apart from a few bloody noses, and we

all ended up together, sharing a case of beer

that someone had thoughtfully produced.

Unknown, Bennie Burke, Paul, DWB. Giza, 1942

But the real enemy was not far away. We had heard much about General Rommel,

and we did not underestimate his leadership, yet

we never seriously considered that he might defeat

us. Even though we were at divisional headquarters,

we had only a hazy idea of the respective strength

and potential of the two armies. Tension and uncertainty

mounted throughout June. By this time Paul and

I had become bored with our lives as dispatch

riders and I had reached the magical age of eighteen

and a half years, so we applied for a transfer

to the South African Air Force. Knowing that the

usual channels would have taken a long time, we

asked Dad to help us (he was then a judge, and

the ‘old boy network’ was very effective).

He did intervene, and we were expecting every

day a signal telling us to return to South Africa

for training as pilots. If the attack on Tobruk

had taken place just a few days later we would

have been on our way south to begin our training.

This thought haunted me (and Paul, though he was

more philosophical about it) throughout the years

of being a prisoner of war. I used to think that

it would have been more glorious, more manly,

to have been a fighter pilot than a prisoner of

war who had done little of any consequence before

being captured. But when we returned to Durban

after the war, I learnt how many of our school

friends – Gordon Henderson, Albert Clarke,

Laurie Chiddell, one of the Shippey boys, and

many others – had joined the South African

Air Force as fighter pilots and had not returned.

At first reluctantly, then gratefully, I came

to prefer being a live non-hero to being a dead

hero.

The twenty-first of June 1942 was a confusing day at Tobruk, starting early with

German aircraft coming in low and firing at us,

and with us fleeing in all directions. This was

the first time we had been under fire. I lost

track of Paul, who had been out with Jake, in

a truck, delivering dispatches. They picked up

some wounded soldiers and took them back to hospital,

then noticed that Piet Pieterse and McAlpine,

another of our DRs, were swimming in the bay.

Paul and Jake called to them to come out quickly,

as the situation was dangerous. The four of them

carried on to the Indian Brigade, unaware that

the Germans had broken through there. They were

hit by a shell from a tank which killed Piet,

severed McAlpine’s arm, and, seriously wounded

Jake in the head and arm – but left Paul

unscathed.

When Paul, thinking that Jake was also dead, returned to find me, I asked where

Piet was. Paul ignored me, just saying ‘Come

on, we’ve got to get out of here.’

I repeated my enquiry about Piet, and this time

Paul, angrily, and close to tears, said, ‘Piet’s

fucking head was blown off. Come on!’

Jake was discovered later the same day by an Italian medical orderly, who had

been sent to the field to see if any men were

still alive. The orderly got him to hospital,

and later he was taken to Italy in a Red Cross

boat and transferred to Parma Hospital. Jake was

later sent to Camp 54, Fara Sabina, where, to

our surprise and mutual delight, we met up again.

Paul and I were strong swimmers, and we had had plenty of recent practice in

the Mediterranean, so we decided to head for the

coast, with the intention of hiding up until nightfall,

then swimming the six miles beyond the perimeter

of Tobruk, from where we thought we could easily

walk until we found Allied troops. Little did

we realise that by then Rommel’s forces

were far beyond Tobruk, and were pressing on to

Alexandria. Four others were with us. Who? I do

not remember, but this was the inevitable ‘little

band of followers’ that Paul attracted,

especially in a crisis. When we were making our

way to the coast, a young second lieutenant, who

had only recently joined our Company, timidly

asked if he could join us. ‘No’, said

Paul, quite brutally, ‘you would only be

in the way.’ The lieutenant then offered

to share his bottle of gin, and this became his

passport to joining our little group.

When we arrived at the rocky coast, we found a small cove, which we thought would

allow us to escape detection from the Fieseler

Storch – an early and very effective ‘short

take-off and landing’ aircraft – which

we could see in the distance, obviously searching

for Allied soldiers. In the confusion of leaving

camp, I was clad only in a pair of shorts, now my only worldly possession. (Today, when I consider

the vast array of possessions which we deem necessary

to make life supportable, I think almost wistfully

of that early liberation from things.) We shared the gin, passing the bottle round from mouth to eager mouth. After

my one-seventh share of the bottle I was drowsy

and, as no aircraft were in hearing or in sight,

I slipped off my shorts and dozed in a convenient

rock pool.

My afternoon reverie was rudely disturbed by a sudden burst of gunfire, very

close, and the appearance, round the corner of

our cove, of two German soldiers, shouting for

us to raise our hands and surrender. I felt as

though I were on stage, naked, and made a dash

for my shorts. This made the nervous Germans think

I was reaching for a gun, and brought another

round of fire, even closer, so this time I very

quickly raised my hands, as the others had already

done. I felt embarrassed, not only at being a

hands-upper, but also because I was ‘starko’ – as though this were not

the right script; people did not get captured

without clothes. Reassured to see that I had no

lethal weapon, the Germans allowed me at last

to put my shorts on. They told us that a Storch

had spotted us, and reported our position and

numbers to a ground patrol, which had been sent

to round us up. They said they would be handing

us to their Italian allies, apologising, ‘We

and you, we are the real soldiers, but the Italians

…’

1942–1945:

PRISONERS OF WAR 1942–1945:

PRISONERS OF WAR

The total strength at Tobruk, including British and Commonwealth troops, was

35 000, of whom 25 600 were captured. Major-General

Klopper, commanding our Second South African Division,

was bitterly criticised, both at the time and after

the war, for surrendering to General Rommel. During

our POW years, there was occasional tension between

British and South Africans, because of General Klopper’s

surrender: later historians exonerated him from

accusations of cowardice, pointing out that he was

out-numbered and out-manoeuvred, and that he had

no choice.

The sheer numbers of prisoners presented great logistical problems to our Italian

captors, who were not well organised at the best

of times. But we were not thinking of logistical

problems, just dully wondering what would happen

and how we would adjust to our new status. Army

life, with its relative loss of freedom, should

have prepared us to some extent for our new state,

but I think most of us just could not imagine such

a total deprivation of liberty. One POW book, The Melancholy State ( Wolhuter, n.d.), uses the phrase adopted by Winston Churchill, a press correspondent

and POW during the Anglo-Boer War in 1899: ‘It

is a melancholy state. You are in the power of your

enemy, you owe your life to his humanity, your daily

bread to his compassion. You must obey his orders,

await his pleasures, possess your soul to his patience

… You feel a constant humiliation in being penned in by railings and wire, watched by armed guards

and webbed about with a tangle of regulations and

restrictions.’

We wondered how long our captivity would last: although we were prisoners for

just under three years, Paul and I seldom believed

that our confinement would last more than six months;

perhaps this optimism was good for our morale.

Of the days immediately after our capture I remember little with any clarity;

it is all a blur of hunger, thirst, dirt, crowded

lorries and general discomfort and anxiety –

and, in my case, a feeling of guilt. Another South

African POW ( Rosmarin, 1990) shared my feelings:

‘After I was captured, I developed a shocking

guilt complex. Hands-upping to the enemy without

any real resistance, I had not fired a shot in anger.’

(In South Africa, a hands-upper was a derogatory term for a member of the Boer forces who surrendered to the

British in the Anglo-Boer War.) ‘It was as

if I had committed a cowardly act. The “chucking

in the towel” haunted me for many months of

my POW career. I had let my country and family down.

I often tried to justify my actions, but always

returned to the same conclusion.’

We were put into large trucks, like cattle trucks, and transported nearly seven

hundred miles west. The first day was the worst,

one of the grimmest of my life, although we were

not treated brutally. I need to stress this aspect,

because the term POW often conjures up images of

movies like The Bridge on the River Kwai, or A Town Like Alice, and the unspeakable horrors of the Japanese camps – or, to take a more

contemporary example, of POWs in Bosnia, or the

US Guantanamo camp in Cuba. We did not endure such

suffering. We were hungry, but for the most part

we were treated in accordance with the Geneva Convention.

When we joined the army we knew of the dangers, although, being young, we never

thought that anything disastrous would happen to

us. Most discomforts that we experienced were the

result of inefficiency, wartime shortages and transport

problems, rather than of any deliberately inflicted

cruelty. And quite often our difficulties and shortages

were shared by our guards, and by most of the enemy

civilian population. In fact, from reading accounts

of other POWs in Italy and in Germany, it is clear

that Paul and I were relatively lucky: some of the

others had much rougher experiences.

We spent the third night of our capture, at Derna (Darnah). We did at least have

some cover – unlike many others – in

a very crowded army barracks. On arrival, we were

put through what was to become a boringly familiar

routine, being assembled in rows of three, told

to march, and counted. The guards kept getting the

numbers wrong, amidst much excited shouting; then

we would have start all over again. Our fatigue,

hunger, bewilderment and general misery all conspired

to make me, and a fellow prisoner, careless. I was

on the right of one of the rows of three, with Arthur

Winter immediately behind me. Each time we were

counted, and recounted, a grimy Italian guard clapped

his hand on our shoulders as we filed past, calling

out the numbers: uno, due, tre, quattro … Arthur and I watched with impatience, scorn and distaste as the inefficient guard

messed up the counting yet again. We also involuntarily

flinched away from his grubby paw. Apparently our

refined reaction offended him, for, when the counting

was eventually completed, he called Arthur and me

out of the ranks, and took us to a small office.

When an officer followed us in, I thought that everything would be alright. I

can still see the small, elegant, unsmiling and

clean young lieutenant, smelling of perfume and

soap, watching us impassively. The guard then struck

me, without warning, a hard slap across each cheek,

and repeated the process on Arthur. As the officer

had ostentatiously taken out his revolver, there

was nothing we could do. The slaps did not really

hurt, what was hurt was our youthful pride. I was

furious – and powerless. When we rejoined

the others (our little gang then numbered six),

Paul was immensely relieved to see me, and to learn

that I had not suffered any dire penalty. Let me

say now that this was the only time that I was struck

during the whole period, so there is no need to

wonder if worse is to come in the way of beatings.

Later that day we were lying on the concrete floor in the barracks, tired, dirty,

hungry and, above all, thirsty, as we’d had

little to drink since we’d been captured.

Then the same guard appeared, obviously looking

for Arthur and me. I turned away, just hoping that

he was not going to call me back for more ‘lessons’.

But he offered me a large water bottle – two

litres, and full. I looked at him with as much scorn

as I could muster, muttering ‘bugger off’,

and determined that I’d rather die than take

anything from this creep (ah, youthful pride). Fortunately,

and not for the first – nor the last –

time, Paul intervened with wiser counsel, reminding

me that I had to think of the others in our little

gang. Some prisoners, we knew, had bartered their

wrist-watches for less water than I was being offered.

So I accepted, with as much grace as I could summon,

and found myself shaking hands with and being embraced

by my new friend. Oh, how good the water tasted,

and how sweet were the remarks of ‘Good old

Dave’, even though I knew that it was really

good old Paul who had saved the day. We rationed

the water carefully among the six of us.

I do not remember how long the rest of the journey took. There were often long

waits and delays, then we would drive along at a

fair speed, passing small Italian colonial farms,

then there would be more stops. It was not a pleasant

trip, and later Bernard told me that, like many

others, I tend to blot out unpleasant experiences

from my memory.

We finally arrived at our destination, Tarhunah, fifty miles southeast of Tripoli,

in what is now Libya, which was to be ‘home’

for the next five months. (In the 1990s, Tarhunah

acquired a notoriety, allegedly having a large underground

chemical weapons plant.) It was a tiny settlement,

an old army camp, with barracks, in which we slept.

The whole camp covered about two acres, with a strong

wire perimeter fence, and soldiers guarding the

six hundred or so POWs. Once again we had our little

syndicate, consisting of Dickie (our senior DR platoon

sergeant), Tubby Trout, a calm cheery Englishman

who had migrated to South Africa before the war,

Stan Smollen, who became my benefactor, and Paul

and me.

Such a group would today be recognised as a ‘support group’. We did

not consciously forge the group for mutual support,

but it undoubtedly served this purpose, and helped

us to keep up our morale. A few prisoners let themselves

go, neither washing regularly nor minding their

general appearance, but our leaders, Dickie and

Paul, were strict about the standards expected from

our elite group, and these included daily bathing

and shaving. We washed, quite satisfactorily, in

a tin-helmet, two thirds full of water, using an

improvised washcloth. We had one razor between the

five of us, and I proposed that I should have first

go, on the grounds that I had the lightest beard,

but Dickie disagreed, and I became the last, often

struggling with a blunt blade. I had no toothbrush,

nor did most of the others, so we used our fingers,

coated with ash. A dentist later told me that this

was an efficient form of dental hygiene.

I acquired a shirt, I do not remember how, but I do distinctly recall being presented

with a greatcoat by Stan Smollen in about September,

when the desert nights were beginning to get chilly.

When it was cold, Paul and I shared one blanket,

snuggling up to keep warm, and the greatcoat was

a blessing. Stan, one of the few POWs who did not

smoke, bartered cigarettes for this greatcoat for

me. When he gave it to me, I had to try hard not

to weep, it was one of the most welcome presents

I have ever had, and one of the most disinterested

gestures I have known, a pure act of love. (Paul

and I met Stan again after the war, at the Wanderers

Club in Johannesburg: he had become a successful

businessman.)

Food was short at Tarhunah, largely for logistical reasons. We were hungry all

the time, and we were seriously alarmed when one

prisoner died of what was said to be beriberi –

certainly as a result of malnutrition. The single

medical orderly used this death to try to upgrade

our diet, but with little success. What I remember

most clearly about the hunger were the dreams, and

the collection of recipes; we all dreamt of food,

telling each other of the mouth-watering meals we

had seen in our dreams. Many started obsessively

collecting and recording recipes, a habit which

I avoided; such indulgences were not tolerated in

our group. Grown men would earnestly exchange recipes,

for anything from chocolate cream cakes to roast

chicken dinners, with the avowed intention of cooking

these delicious meals when they got home. But these

were true South African males, who had never cooked

anything in their lives, and who were most unlikely

even to enter their kitchens when they returned

home. Among this large group of virile young men

there was hardly any talk of sex, and no erotic

dreams were reported: we were too hungry.

We lined up for food in the late afternoon, waiting eagerly, desperately, for

the cooks to ladle watery soup into our bowls. The

cooks were selected prisoners, who received extra

rations, which put them in an invidious position.

When they dished the food into my bowl I noticed

how shiny their arms were, how glossy their hair,

unlike the rest of us, who had dry, parched skin

and hair. I did not resent the cooks having their

privileges, as they were our only connection to

the outside world.

During the five months in Tarhunah we received no mail, no parcels, no visit

from an International Red Cross representative –

all of which later made so much difference to our

POW lives in Europe. Our prisoner cooks were allowed

to go to the local market, with a guard, to buy

supplies. They managed to have brief conversations

with local Bedouin traders, and brought back news,

and rumours. To our amazement, dismay and, at first,

our incredulity, we learnt that the Allies were

being solidly trounced by Rommel; it was not until

the following year that the tide of war turned in

our favour.

The most exciting and hopeful news brought by our cooks was a report of a small

British unit operating in the desert, which was

harassing the enemy behind the lines, and which

had planned to rescue some POWs. Then we had the

dramatic news that Tarhunah camp was one of the

targets, and we were told that if we wished to be

rescued, we had to be ready for some initial walking,

and we also had to save some rations. The latter

was not easy, but we managed to save some non-perishable

scraps of food, and many of us went for long walks

around the inside perimeter of the camp fence, in

preparation for our anticipated rescue. Day followed

day, and nothing happened. Our cooks could only

surmise that the unit’s plans had changed,

probably because they feared that the Italians had

learnt of the proposed attack on Tarhunah.

At Cambridge in 1947, I became friendly with Alex Jandrell, who had commanded

a South African Air Force bomber squadron in the

desert. He confirmed the existence of the Long Range

Desert Tactical Unit, having provided it with support.

Later I read a book ( Shaw, 1945) about the daring

exploits of this unit, and discovered that Tarhunah

had indeed been one of the proposed targets of a

raid, but plans had had to be changed. This was

one of the first of the many disappointments that

we had to endure.

What did we do at Tarhunah? There were few books, as hardly any of us had had

the foresight – or the opportunity –

to bring any, when captured. Paul and I had a copy

of Gone with the Wind, which I read, right through, several times, losing myself for hours in that

convoluted tale of love and war. (We still had that

book in Germany, and towards the end of the war,

Horst Mainz, our camp commandant, asked Paul for

a letter to say that he had treated us humanely.

Paul wrote the letter, and, to hide it from any

zealous Nazi, I sewed it into the binding of GWTW, which Paul gave to Horst.)

A Johannesburg lawyer, Lionel Cooper, then thirty years old, organised a series

of lectures, a sort of primitive POW adult education

college, such as sprung up in most camps. Lionel

was a superb organiser, and persuasive in getting

both speakers and listeners. I attended a series

of lectures on economics, and on law, both given

by Cooper himself. There were also single lectures:

Cooper persuaded many to give at least one talk,

‘Come on,’ he would say, ‘there

must be something in your life that you can share

with us.’ I gave a prosaic talk on the need

for South Africa to produce more goods, and not

to rely on imports.

One of the lectures featured a surprising intervention: the speaker told of his

work with the police unit responsible for preventing

IDB (illicit diamond buying), describing a dramatic

chase on the border of Bechuanaland (Botswana).

During question time, another prisoner followed

up with so many details of this chase that eventually

the policeman said, ‘Ag, it was you I was

trying to arrest,’ and his questioner admitted

that he had been heavily involved with IDB. It was

indicative of how suspended we felt from normal

life, that the man felt no threat in making his

admission.

We also played cards, of course, and a great bridge competition was organised,

the first prize being an unopened pack of fifty

Springbok cigarettes. Although I have not smoked

since 1977, I can easily recall the glittering attraction

of that precious prize – the last intact box

of ‘real’ cigarettes left in the camp,

when most of us had not smoked a real cigarette

for months, having only occasional puffs of inferior

Italian cigarettes when one of our group scrounged

one. Dickie was very strict in that we were never

allowed to barter food for ciggies.

Paul and I had often partnered each other at bridge, and we knew each other’s

style of play intimately, so we had high hopes when

we entered the competition, which was spread over

several days. There was much excitement when we

did well enough in the initial games to get into

the quarter-finals, the semi-finals, and then, oh

what a giddy thrill when we reached the FINALS. No professional game of bridge has ever been more intently scrutinised. We

played on the ground, using a blanket as a table,

watched by a circle of hundreds of men – for

all of us, players and spectators, such events provided

a welcome escape from the pangs of hunger, and anxieties

about the future. We had all sorts of advice from

our group on the day before the big match, and we

were carefully looked after, like prize thoroughbreds.

(‘Come on, Dave, better have an early night,

get a good rest, our big day tomorrow.’) I

do not remember the hands that we played that morning,

over sixty years ago, but I distinctly recall the

thrill when I picked up what looked like a winning

hand, and my elation when Paul’s bidding confirmed

that he could provide good support. There were great

cheers from all when we won.

The cigarettes were meticulously rationed to make them last, with the four of

us (Stan being a non-smoker) sharing one cigarette,

three puffs each: again, as the youngest, I was

last in turn, which I accepted despite having (in

part) won the precious cigarettes. We presented

a few of them to special friends outside our group.

Much as I enjoyed our escapist games of bridge at

Tarhunah, I have seldom touched playing cards since

then. And I have not smoked for thirty years.

Apart from bridge, some prisoners gambled for money, Crown and Anchor being a

popular game. They did not use real money, all of

which had long gone to the Italians in exchange

for cigarettes, or soap. No, the gamblers, in all

earnestness, used IOUs, some racking up debts of

thousands of pounds. After the war some POWs tried

to enforce their gambling debts. Dad had become

chairman of the newly-formed South African Prisoner

of War Relatives’ Association and, with his

legal background, said that these debts were not

legally enforceable – unlike normal gambling

debts – because of the unusual circumstances.

His opinion delighted the losers, and angered those

winners who had thought they would be rich.

What else? Impromptu and non-denominational prayer meetings were held on Sunday

mornings, much better attended than church services

had been before our capture. We all had one, very

urgent prayer for the Almighty, ‘Please, God,

get us out of here, quickly’. Many former

doubters, agnostics and sceptics (among whom I’d

include both Paul and me) attended the services.

At one of the meetings, an earnest Cape farmer prayed

long and loud for rain in the Cape, possibly having

heard that there was a shortage of rain there. Another

impatient petitioner interrupted the prayers: ‘Fuck

the rain, fuck the Cape, just see that we are freed.’

We were single-minded in our needs and desires.

A MEDITERRANEAN CRUISE

By early December 1942, prisoners began to be moved, in batches, to Italy. When

our turn came, we were transported to Tripoli,

where we spent two days at the docks, sleeping

in the open under a bridge.

Some French prisoners had killed, cooked, and eaten a cat – or so it was

alleged, rumours were so rife throughout our captivity

that it was often difficult to know what was true

and what was not. Hungry though we were, this

horrified us, and if we had not been put aboard

our ship, the Col de Lana, that day, there would have been serious riots.

From Tripoli to Naples, where we landed, is less than six hundred miles, but

our voyage lasted five days as we zig-zagged in

order to avoid attacks by Allied aircraft or ships.

The first day or two were bearable: although we

slept in the hold, the guards allowed us to go

on deck fairly freely in daylight hours, until

an RAF aircraft appeared from nowhere, flew low

over the ship, machine-gunning the decks. Despite

being in danger ourselves, we were so overjoyed

to have our first sight of one of our fighter

planes that those of us on deck spontaneously

cheered and waved. The Italians, one of whom had

been wounded, were furious, and kept us below

decks for the remaining three days, not even letting

us on deck to use the ‘over the side’

privy – and there were no facilities below.

The crowded and fetid hold soon became extremely unpleasant, with the movement

of the ship causing all the muck to roll to and

fro. These days were the worst of the war for

Paul. They were bad for me, for all of us, but

for the first time Paul faltered, which worried

me, as he had been my rock. At one time he called

out, ‘God? There is no God.’

The only prisoners who behaved with poise and dignity were a group of Sikhs,

who stayed in a corner, prayed, talked quietly,

and remained imperturbable while ignoring the

incredible squalor and filth all around them.

Ike Rosmarin (1990) reports a similar scene. He

and at least five thousand other recently-captured

POWs were in a ‘disorganised and filthy

cage’ at Benghazi, where ‘a display

of great courage by the turbanned Indian soldiers’

(Sikhs) ‘of the famous 4th Division greatly

impressed. They refused to eat the small portion

of tinned horse-meat as it clashed with their

religious beliefs. They were starving but wanted

no sympathy.’

CAMP 54, FARA SABINA: DECEMBER 1942 TO SEPTEMBER 1943

We arrived in Naples in early December 1942, walking – trying to march

briskly – from the docks, through the streets

to join our transport. A vivid memory is of our

passing Neapolitan women who were weeping, and

suddenly realising that they were crying for us.

It was only then that I felt sorry for myself,

I had not realised what pitiable creatures we

must have looked, undernourished, dirty, in ragged

and threadbare clothing Fortunately, an improvement

was in store for us, as we soon arrived at our

new camp, Camp 54, at Fara Sabina in the Sabine

Hills, twenty miles north of Rome. Here we found

a well-organised camp, with beds, blankets, new

uniforms, showers, reasonable food and our first

mail, as well as our first Red Cross parcels.

Paul and I were overjoyed to be given a large batch of letters, many of them

in Ouma’s dear, familiar handwriting, on

her Basildon Bond blue stationery. We took our

letters to a secluded corner of the camp, so that

we could read them in peace. Although it was December,

it was a clear, sunny day, and we sat on boulders

near the perimeter of the camp. We opened the

letters eagerly, not bothering to put them into

chronological order. We soon realised that something

was amiss, as we anxiously read out to each other

such lines as ‘everyone has been so kind

… people all thought so highly of Guy …

what will become of dear Margaret and Deirdre?’,

neither of us wishing to accept what each phrase

made more certain – that Guy was dead. Today,

more than sixty years later, I easily recapture

that awful moment with all its details. To me

Guy had seemed invincible, I never thought that

he might die. We dragged ourselves back to our

fellows and told them the news. There followed

an endless procession of friends, and others whom

we hardly knew – they all knew about our

heroic elder brother Guy. They solemnly shook

our hands, muttering ‘Sorry Paul …

sorry Dave.’

When we met Dad in Brighton after our release in May 1945, we learnt that Guy

had been serving on the aircraft carrier HMS Formidable, on convoy duty between Mombasa and Colombo in Ceylon (now Sri Lanka). He had

been due to return to Britain where he would have

been stationed in Wick, Caithness, with his own

squadron and where he would have been reunited

with his wife Margaret and seen his baby daughter,

Deirdre. Guy had seen Deirdre only once –

soon after her birth in January 1942, when he

was on 48 hours leave; he took a taxi from Wick,

but snow blocked the way and he walked the last

few miles.

The senior pilot of 888 squadron was Guy Brockensha [sic], an RN lieutenant, handsome and of great charm, who had won a DSC in Norway

flying Skuas and was our guide in South Africa

since he hailed from Durban where his father was

a judge. On August 6th 1942 occurred a mysterious

tragedy to which no satisfactory answer has yet

been given. Guy Brockensha disappeared from the

ship during the night. Before anchoring in Mombasa the ship was searched thoroughly but no

trace was ever found. An enormously popular Lieutenant

RN, already decorated with the DSC, he was an

excellent pilot, a good sportsman and so far as

any of his closest friends knew Brock hadn’t

a care in the world. He was happily married to

a beautiful Scots wife in Wick … In over

forty years since his mysterious disappearance,

no satisfactory explanation has ever been offered.

The whole ship was depressed over the loss of

this popular and brave shipmate … Finally

on 24th August we left Mombasa and proceeded to

Durban where Brockensha’s parents came aboard

and spoke to all his close friends. A very sad

interlude, with little that we could say, except

to offer condolences. At least they left the ship

knowing that they were parents of a very fine

and brave son.’ ( Woods, 1945) .

![]()

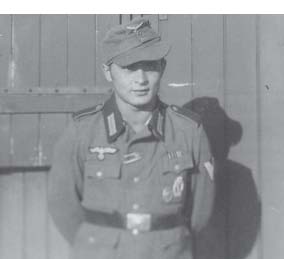

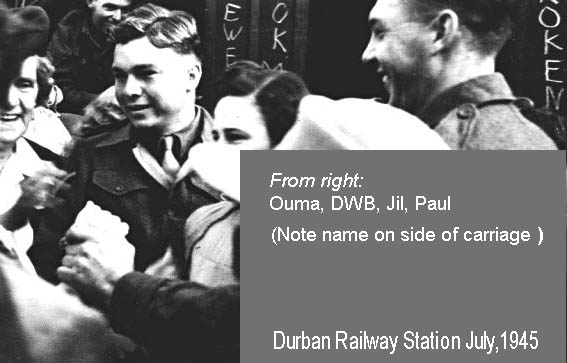

TOP: Guy and Margaret on their honeymoon. 1940 ABOVE: Guy, in the centre. Fleet

Air Arm, 1941

Dad told me that he had spoken to the ship’s captain, also to the surgeon,

who mentioned that Guy had complained of abdominal

pains, the surgeon suggesting that Guy get checked

out when next in port. He could only surmise that

perhaps Guy had felt sick and had gone to the

side – he slept on the open deck of the

aircraft with just a low guard rail – had

lost his balance and fallen overboard during the

night.

I was reluctant to accept that Guy was dead. After all, I told myself, he was

a champion swimmer, perhaps he had swum for hours

and then reached the shore but had suffered amnesia.

For nearly thirty years he used to appear in my

dreams, looking older, and asking, ‘Dave,

don’t you recognise me?’

Returning to our POW camp, and on a happier note, we were overjoyed to see the

first of the all-important Red Cross parcels,

which we were to receive, with occasional interruptions,

for over two years. The contents varied a little,

most of the ones we received coming from the Canadian

Red Cross, neatly packed cardboard boxes of about

15" � 8" �6", each

weighing 11 lbs, and divided between two men.

Sometimes, when supplies were short, more than

two men shared one parcel. They contained tins

of Klim (powdered milk), salmon, sardines, Nescafé,

corned beef, meat roll, jam, butter, packets of

plain biscuits, cheese, tea, salt and a slab of

Neilson’s chocolate.

When we received these ever-welcome parcels, we were on a better diet than most

civilians in either Germany or Britain. We knew

that the Germans lacked many of our luxury items,

and a thriving trade in coffee and chocolate soon

sprang up, but I did not realise, until after

the war, how privileged we were compared to the

British. Paul and I shared our parcel, and later,

in Germany, I shared with Jake; we trusted each

other completely, and never quarrelled over the

division of the contents, as some others did.

After our hungry months, a few men were still

obsessed by food, and would watch their partner

jealously to see that they were not cheated of

one raisin, one sliver of chocolate, one pat of

butter. In such cases, the solution (Solomon’s,

originally) was to take turns, one dividing the

food, the other choosing his share; but even with

this system there were still arguments, as decisions

had to be made as to when to open each item. We

also received a few most welcome book parcels,

and, if they were not stolen, cigarette parcels

– sent by our families.

SG Wolhuter, also a South African POW, dedicated his book to ‘The International

Red Cross, without whose merciful work many of

us would not have survived the prison camps of

Italy and Germany’. He wrote, ‘We

were dumbfounded when we first saw the contents

of a Red Cross parcel, which contained luxuries

beyond our wildest dreams. I am convinced that

without them few of us would have survived the

internment in prison camps for nearly three years

and our gratitude was such that no man who experienced the benevolence and charity

of the International Red Cross is ever likely

to believe that there is a more worthy cause in

the world’ ( Wolhuter, n.d.: 39).

and our gratitude was such that no man who experienced the benevolence and charity

of the International Red Cross is ever likely

to believe that there is a more worthy cause in

the world’ ( Wolhuter, n.d.: 39).

Similarly, another POW writes, ‘it was when we received our first parcels

from the Red Cross that our hungry days were forgotten

… on my return to South Africa in 1945

I joined the SA Red Cross Society, carrying out

my POW vow. My wife and I have up to now 90 years of combined voluntary Red Cross service. I have tried

to repay my debt to Red Cross in this way …

However, if I live another hundred years I could

never completely erase what I owe Red Cross. Nor

can any former POW’ ( Rosmarin, 1990: 103).

Jake.

Fara Sabina, 1943

Harry Mortlock, who had been in Tarhunah with us, was in poor shape when he was

re-united with his older brother Jack, who had

been in Camp 54 since August 1942. After that

they stayed together, like Paul and me, for the

rest of the war, coming to the same camp as we

did in Germany, where we became close friends.

As far as I know, Harry and I are now the only

survivors of our POW group.

Soon after we arrived in Italy, the Allies invaded Sicily, and we were convinced

that in a matter of weeks, or months at most,

we would be freed. Perhaps for this reason there

was, surprisingly, hardly any organised educational

activity, no ‘camp university’ such

as had existed at Tarhunah. Partly to pass the

time, partly to ‘improve myself’,

I took individual French lessons from an English

prisoner, Jack Needle, who had been a schoolteacher

in Ipswich. Jack and I found a quiet place near

the boundary fence for our lessons; he was an

effective and a patient teacher whose lessons,

without textbooks, provided me with a basic foundation

in French. (I tried to make contact with Jack

after the war, when I arrived in Cambridge in

1947, but without success.)

We were not obliged to work in Italy, but farm labour was available on a voluntary

basis. This had two main attractions: workers

received extra rations – even with the Red

Cross parcels we often felt hungry – and,

second, it gave us a chance of getting out of

camp, of seeing new places, even seeing some girls.

(A sign of improved nutrition was a marked increase

of interest in, and talk about, sex). Some Afrikaner

prisoners, farmers themselves, worked on the Italian

farms whenever possible, preferring the rhythms

of the familiar agricultural routine to the boredom

and monotony of camp life. I went on several occasions,

especially in the warmer weather of spring and

summer. I enjoyed the bumpy ride in the old lorry,

passing fields and villages, but the biggest draw,

for me, was the possibility of a swim in the River

Tiber, which adjoined some of the farms where

we worked.

We persuaded our easy-going guards to let us swim in the river during their midday

siesta, evolving a simple strategy whereby they

could enjoy their snooze without fear that we

might escape. We would strip, and place our clothes

and shoes in a big pile, which provided the guards

with a comfortable pillow for their siesta. (Later,

I thought that the sleeping guards in the fields

looked like figures from a Brueghel painting.)

We had no chance of escaping: naked, and with

at best a rudimentary knowledge of Italian, we

would not have got far. Twenty of us would dive

into the swift-flowing Tiber – then crystal

clear and unpolluted – and swim to the end

of the field, the rapid current carrying us swiftly

along. Then we would run back along the bank of

the river, a half-mile, to repeat the process

again and again until it was time to dress and

start work. What wild whoops there were when an

unsuspecting peasant girl entered the field during

our midday revels; once, I distinctly saw one

girl covering her face with her hands, but discreetly

gazing at us through the lattice of her fingers.

Lovely carefree moments, these plunges in the

Tiber are among the happier memories of my captivity.

A less happy recollection is of being plagued by lice, an affliction mentioned

in all accounts of POW life. One vivid picture

comes to mind, of a line of a dozen of us, sitting,

with bare torsos, outside our huts, backs to the

wall in the wintry sunshine, all earnestly ‘reading’

our shirts – one man remarked that we looked

like a row of serious old men reading their morning

newspapers – and dispatching our unwanted

visitors. This plague did not last long.

During the summer of 1943, rumours abounded about the progress of the Allies

in southern Italy; we all felt sure that any day

would see the welcome sight of Allied troops coming

to free us, little realising that much fierce

combat lay ahead. On 9 September the Italians

signed the Armistice, and we were convinced that

our days of captivity were over. The camp guards

disappeared at the first word of the Armistice, so we simply walked out of the camp. Later when

asked if I had escaped, I had to say that it was

a very technical escape, one that happened by

default, not by any heroic or ingenious act on

our parts. Once again, Paul had his ‘little

band’, eleven of us forming a group and

deciding to hide in the fields for a few days

(the gloomier ones thought it might take a few

weeks), relying on local peasants to help us survive

until the Allies reached us. We had no inkling

of the amount of resistance which would be offered

by the Germans, aided by the few carabinieri who had not surrendered.

While we had been prisoners I used to look over the fence at a picturesque Italian

hilltop village, a few miles away, and think how

impossibly remote and romantic it looked. Now

we were able to walk the few miles to the fields

of this village, Monte Libretti, and find a remote

part of a fig orchard where we thought we could

lie low. Even today, when I taste a ripe fig,

I am transported back to that beautiful happy

valley, when our hopes were so high, and we had

no premonition of the bleak days that still lay

ahead. The orchard’s owner soon found us,

and befriended us, bringing us food every day

when he came to work in his fields. He was particularly

kind and protective, urging us to take care, and

to watch out for the few carabinieri who had stayed loyal to the Germans and who were, he warned us, still a threat

to us as they were actively rounding up prisoners

who had escaped from Camp 54. But in our new-found

freedom and our youthful optimism we did not heed

him.

The highlight of our brief stay in the fields – it lasted eleven days –

was a nocturnal visit to our friendly host, who

invited us to his home in the village. He called

for us after dark, when we had made ourselves

as presentable as we could, and led us, very silently,

through the fields to a main road. On that moonlit

evening, I felt a tingle of excitement and anticipation

as we scrambled up a steep bank, paused, then

scurried across the road; then he led us, up a

steep, winding path, to his house in the village.

It seemed that we were back in medieval days when

we passed a group of smiling women, their skirts tucked up, stamping the wine grapes barefoot. Our host produced

the best meal we’d had since our capture.

Not only was the simple food excellent and plentiful,

but there was wine, a warm welcome from the large

family, and lively conversation – as best

we could with our limited Italian. Paul got on

well with Valentina, the fifteen-year-old daughter,

who was casting shy, admiring glances at this

bold, handsome stranger during the dinner. It

was an important occasion for us, as it removed

Italians from the pejorative stereotype ‘Iti’

(pronounced eye-tie) and introduced us to kind, brave, real people.

Perhaps two days, later our host warned us more emphatically about the Germans

and the carabinieri, saying that they had information about prisoners who were hiding in the vicinity.

He told us to hide during the day, in small groups,

and to take every precaution not to be discovered.

He promised to keep bringing us food, but told

us that he was already under suspicion of feeding

escaped prisoners.

Paul, Jake and I hid in a rough shed, full of haystacks. We moved some of the

stacks towards the entrance, leaving us a small

space behind, where we hid, knowing that we could

not be seen from the entrance. A few hours after

we had hidden ourselves, we heard shouts as two

carabinieri approached and started poking their bayonets into the haystacks. Paul and I,

who were nearest the door, surrendered, indicating

to Jake that he should stay and take his chances

without us. But the carabinieri demanded that the third man come out, and Jake had to give himself up, too.

Jake later wrote, ‘When I came out from

the back of the hay and approached Paul and Dave,

Paul whispered “shall we jump them?”

I said, “Look what is in my guts”

– the Italian had his .45 pressing into

my stomach.’

I first thought, bitterly, that our host had betrayed us, but when Paul and Jil

visited Monte Libretti in 1960 they had a warm

welcome from the family, and learned the full

story. The carabinieri had noticed that our host was taking out large amounts of food to the fields

and guessed that he was feeding Allied prisoners.

They beat him and threatened terrible reprisals on his family, particularly on his daughter,

Valentina, and he was forced to tell them where

we were hiding. When Paul told me this, I was

ashamed for having for years held onto unreasonable

bitterness at what I’d imagined was a betrayal.

Paul also reported that the lovely young Valentina

had become a stout matron, with missing teeth,

and Jil teased him about his Italian sweetheart.

Then began an agonising and traumatic day for me. If Paul’s worst day was

in the hold of the Col de Lana in the Mediterranean, then mine was that day, 20 September, when we were recaptured.

I can now be more analytical, and see that I was

completely unprepared for another spell in a POW

camp, so sure had I been that freedom was around

the corner.

One of the few men from Camp 54 who succeeded in reaching the Allied lines was

an Afrikaner, a quiet, and, we thought, a rather

simple Free State farmer, who saw no reason to

rely on the British and Americans reaching him,

but instead set out to reach them. Against this

emergency, he had saved a supply of cigarettes